Pure existence (Shiva) is pure consciousness (Shakti), consciousness is the dynamic aspect of Shiva, that is conceived and described as his Shakti. This Shakti is not conceived as any distinct attribute or quality or any special feature of Shiva. Shiva’s Shakti is no other than Shiva himself. In this transcendent nature Shiva appears as if without Shakti, since she has no outer expression in that state. But in reality Shakti is not then altogether absent. The dynamic aspect of Shiva is then perfectly identified with and is distinguishable from his transcendent aspect. In his phenomenal self-expression the dynamic aspect is more predominant; Shiva then reveals himself as Shakti. The manifold self-expressions of Shakti in the spatio-temporal order are also essentially non-different from Shakti and hence from Shiva. The world process is conceived by Veerashaivism as Shiva-Shakti vilasa or sidvilasa; the spirit in playful garbs and the tidal wave of bliss and beauty.

The metaphysical theory of Veerashaivism is known as Shakti vishista advait. It maintains that what exists is alone cognized and that there is no bare negation. The absolute is not Shiva versus Maya but it is all Shivamaya. Reality and value are one and the more real a thing is, the more true it is. Shiva is eternal, pure and perfect and is the supreme. According to a Veerashaiva philosopher Shiva is the source and support of all phenomenal existence; the basis and goal of all terrestrial evolution. Empirical reality or phenomenal manifestation is the imperfect unfolding in time of an eternally complete self-existent Shiva or Sthala. Sthala is therefore the infinite and eternal rest into which all motion and dialectic are absorbed. The ultimate expression of this eternal being is self-consciousness. The question now arises: ‘Does not consciousness presuppose that which becomes conscious?’ Veerashaivism believes that it does. The synthetic unity of consciousness, that is, the logical element presupposes the illogical element, the I or the principle which becomes unified. This principle of “I-ness” or Ahamta, when considered per se, may be regarded as the matter of which thought consciousness is the form. Now this material moment has been ignored by many leaders of speculation and appearance of having transcended the distinction has been obtained by the hypostasis of form, the logic from its illogical matter, the hylo. He contends that the ultimate all-penetrating material moment gives us the aspect of being which is Shiva; the formal and actual moment gives up the aspect of knowing which is Shakti.

There is not an unbridgeable gulf between being and knowing; for to know is as necessary as to be. If we admit a gulf between being and knowing, then the theory of Reality is sundered and an element of discrepancy creeps in. This tendency is discernible in the Kantian opposition between the noumenal and the phenomenal reality, the Bradleyan contrast between reality and appearance, Shankara’s distinction between the transcendental and the empirical. Veerashaivism avoids this impasse by accepting the trustworthiness of knowledge in all its four levels. The logical apprehension of Shivajnana as supremely real, leads to the intuitive realization of Shivanubhava.

In Veerashaivism, Sthala has a philosophical connotation. The letter stha denotes the source from which the phenomenal world emerges and draws its substance; and the letter La denotes the goal to which it tends and in which it ultimately loses itself. The Svarupa if Shiva is Sacchidananda and this nature of Parashiva is well expressed in terms of his self-consciousness and bliss. The Divine is self-luminous, so is a jewel; but the jewel is not conscious of its luminosity, while the divine is both self-luminous and conscious of his self-luminosity. It is this self-consciousness of Shiva that goes by the name of Vimarsha, Atmavimarsha and Paramarsha whose characteristic is that in it consciousness and energy, knowledge and force are one.

Vimarsha Shakti exists in Shiva by the relation of Samarasya or identity, just as heat and light exist by the relation of identity in the fire and the sun. In other words, between the substance and the attribute there is an inseparable union or essential identity which points to reality that continues to remain in the character of individual organic Whole. It is for this reason that Siddanta Shikhamani speaks of intrinsic and ever abiding in Shiva. Hence he is characterized and distinguished by his self-conscious power to work wonders. This is Shaktivishistadvaita. Here Vishista does not suggest any inseparable union of two or more entities like soul, world and God of the Ramanuya system or of South Indian Shaivism. Vishistattva simply connotes the nature of Vimarsha, namely the self-conscious power of Shiva. Because of this Divine energy or Chit-shakti which has the power of doing, undoing and doing otherwise, Shiva transforms Himself into the world without ceasing Himself to be. Hence, Veerashaivism maintains Shivaparinamavada.

The theory of causation is known as Satkaryavada. It is a theory as to the relation of an effect to its material cause. This theory maintains that an effect originally exists in the material cause prior to its production. So the Sankhya causation means a real transformation of the material cause into the effect and this logically leads to the concept of Prakrti as the ultimate cause of the world of objects. The Sankhya, Yoga, Vedanta and Agamic schools uphold Satkaryavada – the doctrine of identity of cause and effect. Though there is an agreement as to the theory of causation among those schools, yet there is a divergence in their metaphysical conclusions. The Satkaryavada has two aspects – Parinamavada and Shivartavada. According to the former, when an effect is produced, there is a real transformation of the cause into the effect, that is, the production of a pot from clay or of the curd from the milk. The Sankhya is in favour of this view. The second view, which is accepted by the Advaita Vedanta, holds that the change of the cause into the effect is merely apparent when we see a snake in a rope, it is the case that the rope only appears as a snake. So God or Brahman does not become really transformed into the world produced by Him but remains identically the same, while we wrongly think that he undergoes change and becomes the world. Shankara therefore argues that evolution of the objects that constitute the world is illusory and Brahma is but the seeming material. “Brahman becomes the substratum of all phenomenal changes like evolution etc., superimposed on him by avidya; in his real nature he remains beyond all phenomenal changes.” Ramanuya attributes to Brahma even in his causal state, a subtle body made up of individual souls and Prakrti that have become absorbed in Him. During the material state, when the world is in manifestation, it is this body of His that evolves, He Himself remaining untransformed.

In the case of Sankhya and Ramanuja, it is Prakrti Parinamavada but in Veerashaivism it is Shiva Brahma parinamavada. The world comes out of the very essence of Shiva and not from maya, or body or even power of God as found in the other systems. In upholding the doctrine of the transformation of essence (svarupa parinamavada), Veerashaivism remains most faithful to the Scriptural authority. God happens to be both the material and efficient cause of the world, though God becomes the world by the process of modification. He does not suffer any change within Himself. The world is the Sat-aspect of God and therefore a real manifestation of Him and not an illusion. It is non-different from Him; the relation between the two is that of the identity of cause and effect. The world gives us an idea of the greatness of God, and those who realize this greatness cannot but worship Him. In the words of Hegel, the reality of the world supplies the individual with the religion of majesty in which the reflecting mind is overwhelmed by the contemplation of the manifestation of the Divine Being.

On the strength of Svarupa-parinamavada, Veerashaivism conceives the spirit of God as absolutely perfect (Shiva) and infinitely dynamic (Shakti). Shiva is pure existence and pure existence is the characteristic of Reality. It indicates not only the negation of non-existence but also the negation of all forms of imperfect existence. Such a state of experience may appear as void or shunya to the men of normal or empirical experience, but that transcendent state of experience is the state of perfect fulfilment of all earnest endeavours for liberation from all limitations and realization of the Absolute Truth. Pure existence (Shiva) is pure consciousness (Shakti), consciousness is the dynamic aspect of Shiva, that is conceived and described as his Shakti. This Shakti is not conceived as any distinct attribute or quality or any special feature of Shiva. Shiva’s Shakti is no other than Shiva himself. In this transcendent nature Shiva appears as if without Shakti, since she has no outer expression in that state. But in reality Shakti is not then altogether absent. The dynamic aspect of Shiva is then perfectly identified with and is distinguishable from his transcendent aspect. In his phenomenal self-expression the dynamic aspect is more predominant; Shiva then reveals himself as Shakti. The manifold self-expressions of Shakti in the spatio-temporal order are also essentially non-different from Shakti and hence from Shiva. The world process is conceived by Veerashaivism as Shiva-Shakti vilasa or sidvilasa; the spirit in playful garbs and the tidal wave of bliss and beauty.

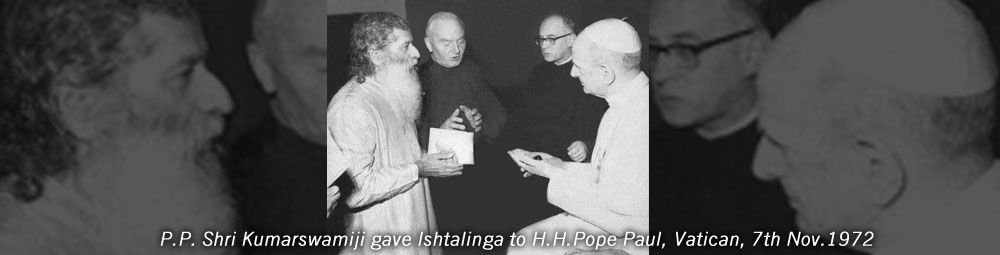

This article – The Metaphysical Aspects of Veerashaivism – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Prophets of Veerashaivism’.