The Grace is, in the words of the Sharana like a perfume; the more it is pressed, the sweeter it smells. It is like a star that shines brightest in the dark. It is like a tree which, the more it grows, the deeper root it takes and the more fruit it bears. As heat and cold, light and darkness cannot live together so Grace and sin cannot dwell together in the heart of man. Grace descends into the heart of him who is pure and free from selfishness and fear. But the descent of the Grace is in gradual hierarchy, its pace is serene and silent, at times it may be abrupt and amazing. “Grace comes into the soul”, says the Sharana, “as the morning sun into the world; first a dawning, then a light and at last the sun in his full and excellent brightness.”

In the twelfth century in Karnatak there was a galaxy of Lingayat Saints, the pre-occupation with whom was to realize God and to remould the individual life and social institutions by that realization. To know, be and possess the Divine Being in the discursive individual consciousness, to convert the illusions of desire into illumination of joy, to transform half-lit mental obscurity into an ordered intuition, to recognize freedom in a group of mechanical necessities, to realize the immortal life in this earthly tenement which is subject to change and mutation, to build peace and the self-existent bliss in a society paralyzed by physical pain and emotional suffering � this was the promised they offered to the posterity. The number of these Lingayat Saints or Mystics, that is, the Sharanas ranged from two to three hundred amongst whom there were about sixty women mystics, of whom Akka Mahadevi was the beacon-light. She could stand in comparison with any woman mystic either of India or abroad, but excelled all in point of her astounding asceticism to realize God. Basava and Allama Prabhu were the two distinguished names that shone in the firmament of the Lingayat Faith. It was they who dominated all the other saints and gave a decisive turn to the religious renaissance of the twelfth century. Almost all the saints have sung their realization in different strains and expressed their views and opinions on men and society in varied sayings. The collection of these sayings is known as the Vachana Shastra � the Scripture of the Lingayat Faith. The sayings of Basava are characterized by the sublimation of elegance, the apotheosis of merit, the transfiguration of grace. But in reading the sayings of Allam Prabhu, we seem to be the spectators of a ‘life-drama’ and on-lookers of a Master Spirit’s progress and development through the stress and stir of the eternal yea and nay. This spirit of detachment and idealism is manifested throughout his sayings whose cryptic expression surpasses in a way that of Carlyle in his Sartor Resortas, Shakespeare in his Sonnets or Tennyson in his In Memoriam.

The Vachana Shashtra is the fruit of deep meditation and mature observation of many a Lingayat Saints. It contains true sublimity, exquisite beauty, pure morality and fine strains of poetry. In what-so-ever light we may regard the Vachana Shastra, it is found to be a valuable mine of knowledge and virtue. The more deeply one works the mine, the richer and more abundant he finds he ore. More light continually beams from this scripture to direct the conduct and to illustrate the work of God and the ways of men. As all the scriptures of the world, it teaches us the best way of living, the noblest way of suffering and the most comfortable way of dying. The importance and value of the Vachana Shastra cannot be too greatly emphasized in these days of uncertainties, when men and nations are prone to decide questions, from the stand-point of expediency rather than in the light of eternal principles. Scholars may quote high authorities in their studies, but the hearts of thousands will recite the Vachanas at their daily toil and draw strength from their inspiration as the meadows draw it from the brook. A wide-spread interest and admiration is displayed in the Vachana Shastra now-a-days by the Lingayat Community; but a mere interest or admiration without an insistent application of truth to life is as good as a pig in the flower garden. The Vachana Shastra is to the Lingayat Community what the star is to an astronomer; but if the Community spends all its time in gazing upon it, observing its motions and admiring its splendour, without being led into its spirit, the use of it will be lost to the Community. On the whole, the truths of the Vachana Shastra have the power of awakening an intense moral feeling in every human being. They send a pulse of fellow-feeling through all the domestic, civil and social relations and teach men how to love the right and hate the wrong. They seek each other’s welfare in the right sense of self-sacrifice but not in the shadow of enlightened self-interest. They control the baneful and bastard passions of the heart and thus make men proficient in self-government. Finally they teach man to aspire after God and fill him with hopes more putrefying, exalted and conformable to his nature so as to secure an intuition of the Supreme Being.

The Vachana Shastra or the scripture of the Lingayat Faith depicts the Supreme Being or God as an eternal, infinite and incomprehensible being, the creator of all things, who preserves and governs every event by his almighty power and wisdom and who is therefore the only object of worship. To the Lingayat Saint or Sharana, as also to all the mystic alike, the presence and love of God are always before his mind’s eye. He makes incessant efforts to establish a direct relation to God, so that his ever-repeated call for Samarasya, that is atone-ment indicates nothing but an approach to Divien Reality. Thus the life’s philosophy of the Sharana cannot be summarized better than in the words of Dr. E. Carpenter: “God is through all in all, so that life and limb are His through all in all, so that He breathes in our breath, speaks in our speech, thinks in our thought. What then? Shall we suffer and He not know? Are we in pain and will He not feel? It is the mystery of His nature to the eternal and the all-pervading and yet to blend Himself with our mortal frame, and to abide unchanged while we grow and decay.” Thus we see that the Sharana realizes God through intuitive feeling. He thinks but he thinks with the heart; this thinking with the heart takes him on to the secret existence of God. His arguments about the existence of God are simple, straight-forward and yet cogent enough. “The world we inhabit must have had an origin; that origin must have consisted in a cause; that cause must have been intelligent; that intelligence must have been Supreme; that Supreme intelligence is God.” The Sharana out-bursts in a sentimental, albeit serene tone. “Since God is the Supreme intelligence, he is the light of my understanding, the joy of my heart, the fullness of my hope, the mirror of my thoughts, the consoler of my sorrows, the guide of my soul through this gloomy labyrinth of time, the telescope to reveal to the eye of man the amazing glories of a far distant world.” The gift of thinking with the heart drives one towards the integrality of a higher nature, a purer conscience by virtue of which he enters into the communion with God. How often we look upon God as our last and feeblest resource! We go to him because we have nowhere to go. We fret and fume, we wail and complain, we stress and stir only to learn that the storms of life have driven us not upon the rock, but in the inmost recess of Reality. A mystic has said elsewhere: “God is an un-utterable sigh in the inner-most depths of the soul” With still greater justice, we may reverse the proposition and say, ‘The soul is a never-ending sigh after God’ If so, God should be the object of all our desires, the end of all our actions, the principle of all our affections, and the governing power of our whole souls. Thus observes Washington: “It is impossible to govern the world without God. He must be worse than an infidel that lacks faith, and more than wicked that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge his obligation.” Because God is the governing power of the world, He is represented as the figure of an eye upon the scepter, to denote that He sees and rules all things. “In all thy actions”, says the Sharana, “think that God sees these and in all His actions labour to see Him. That will make thee fear Him and this will move thee to love Him. The fear of God is the beginning of knowledge, and the knowledge of God is the perfection of love.” It is this refreshing knowledge and redeeming love that impels one not only to realize the presence of God in all events and movements but also obliges him to attune his action and attitude to the will of God. This is therefore the vade mecum of the Sharana: “In all His dispensations God is at work for our good. In propensity He tries our gratitude; in mediocrity our contentment; in misfortune our submission; in darkness our faith; under temptation our stead-fastness; and at all times, our obedience and trust in Him.”

God is the Alpha and Omega of the Mystic; to him He is a transcendental Reality whose energy is immanent in the universe. It is the stress of this energy that shapes things, guides the course of events and pre-ordains the world-process. The energy that manifests itself in the workings of the world is cosmic will which is sometimes known by the name of Nature, that is purposive and therefore determinant. But God transcends this cosmic will by his Supreme Will which is spontaneous and has the power of doing, undoing and doing otherwise. God is therefore more than Nature. Still Nature is man’s teacher; she teaches the individual to universalize himself and then to transcend the cosmic formula. She trains the unruly personal will of man, unfolds her treasures to his search, unseals his eye, illumines his mind, and purifies his heart. She is a frugal mother who never gives without measure, never wastes anything. She undergoes a succession of changes so gentle and easy that we can scarcely mark their progress. “In Nature”, says Shaftsbury, “all is managed for the best with perfect frugality and just reserve, profuse to none, but bountiful to all; never employing on one thing more than enough, but with exact economy retrenching the superfluous and adding force to what is principle to every thing.” Hence the laws of nature are just terrible. There is neither week mercy nor favouritism in them. Cause and consequence are inseparable and inevitable. The elements have no forbearance. The fire burns the water drowns, the air dries, the earth buries. There is then no trifling in nature. She is always true, grave and severe. She is always in the right and the faults and the errors fall to our share. She defies incompetency, but reveals her secrets to the competent, the truthful and the pure. Says Whipple, “Nature does not capriciously scatter her secrets as golden gifts to lazy pets and luxurious darlings, but imposes tasks when she presents opportunities and uplifts him whom she would inform. The apple that she drops at the feet of Newton is but a coy invitation to follow her to the stars.” In all the cosmic movements we thus see at work the great regulative Idea. The ignorant man marvels at the exceptional, but the wise man marvels at the common for, to him the greatest wonder of all is the regularity of Nature.

The Sharana or the Mystic represents God as the eternal, infinite and imperishable Light, as the great Sun of truth and righteousness of whose innumerable rays nature or law is but a single ray Natural law is therefore a method of operation, not an operator. A natural law, without God behind it, is no more than a glove without a hand in it. The laws of nature are not as some modern Naturalists are wont to suppose, iron chains by which the Almighty God is bound hand and foot. They are, according to the Sharana, rather elastic cords which He can lengthen or shorten at his sovereign will. The progress in natural sciences has tended more to the omni-potency of natural law. Determinism has furnished extra-ordinarily satisfactory explanations of physical and biological phenomena, and as the cosmic will finds its expression in definite physical and biological occurrences, it is natural to extend the principle of determinism to cover willed as well as unwilled events. On the other hand, the doctrine of evolution has lent some support to the idea of the freedom of will. If man has evolved from animals of a lower mental organization mainly as the result of natural selection, it is difficult to see why his consciousness should have evolved if it is merely looker-on in the game and cannot actively influence events. A far more important assault has been made on determinism by Heisenberg and other physicists. They claim that while causality applies to large bodies, it does not apply to atoms. Eddington has attempted to identify this atomic indeterminism with the freedom of will. He regards the human body as a device for magnifying its effects from the atomic to the visible scale of magnitude. It is true that one cannot ascertain that an atom in a given situation will behave in such and such a manner merely that there is a certain probability that it will do so. But if we observe a body containing a million million atoms, these probabilities coalesce to a practical certainty. Hence indeterminism for atoms involves practical determinism for large bodies, even if atomic events are really independent of one another. This is the verdict of physics.

In the field of metaphysics we also envisage both these principles of determinism and indeterminism. That nature is strictly determinant, that it abhors favourtism has been proved already. So long as man works in the region of necessity, he is caught in the roving rocket of nature’s law and is enslaved to destiny. What Omar Khayyam symbolizes as the ‘Moving hand’, the ‘Eternal Saki’, the ‘Wheel of Destiny’ is simply the nature’s force that pre-conditions everything. The poets who pin their attention upon this nature’s force as the be-all and the end-all have been generally pessimistic in their out-look upon life, and sing in the doleful strains that the human life has come into existence by the movement of a blind mechanical power, with no charm in matter nor chastity in mind. But the mystic intuits that the supreme will of God transcends the natural laws or limits and behaves independently as an atom behaves independent of one another. When man steps out of the region of necessity and steps into the region of sincere and selfless sympathy that is love, by affiliating his individual will to the supreme will of God, he gets over the tyranny of natural laws and gains freedom not from the law but in the law. This loving afflictions lets the supreme will descend into man by virtue of which he transforms his life human into the life divine. It is this supreme will that goes by the name of Grace in mysticism, whose touch converts difficulties into opportunities, whose presence vanquishes the apparently inexorable destiny of man.

The Grace is, in the words of the Sharana like a perfume; the more it is pressed, the sweeter it smells. It is like a star that shines brightest in the dark. It is like a tree which, the more it grows, the deeper root it takes and the more fruit it bears. As heat and cold, light and darkness cannot live together so Grace and sin cannot dwell together in the heart of man. Grace descends into the heart of him who is pure and free from selfishness and fear. But the descent of the Grace is in gradual hierarchy, its pace is serene and silent, at times it may be abrupt and amazing. “Grace comes into the soul”, says the Sharana, “as the morning sun into the world; first a dawning, then a light and at last the sun in his full and excellent brightness.” Since the Supreme Being is free in his movements, the descent of the Grace cannot be ascertained in definite laws. Hence it is expressed as a mystery. A mystery is something of which we know that it is, but we do not know how it is. While reason puzzles itself about mystery, faith turns it to daily bread and feeds on it thankfully in hear heart. It has been well said that a thing is not necessarily against reason, because it happens to be above it. Jeremy Taylor observes thus: “In dwelling on divine mysteries keep thy heart humble, thy thoughts reverent, thy soul holy. Let not philosophy be ashamed to be confuted, nor logic to be confounded, nor reason to be surpassed. What thou canst not prove, approve, what thou canst not comprehend, believe; what thou canst believe, admire, love and obey. So shall thine ignorance be satisfied in thy faith and thy doubt be swallowed up in they reverence, and thy faith shall be as influential as sight. Put out thine own candle and then shalt thou see clearly the sun of righteousness.”

Mysticism may then be defined as an art to experience unmixed and pure delight in all the contents of the cosmos through intuitive faith in the workings of the Supreme Being. If Epicureanism is human nature drunk, Cynicism is human nature mad, and Stoicism is human nature in despair, then Mysticism is human nature in delight. “Learn thou of pure Delight and thou shalt learn of God.”

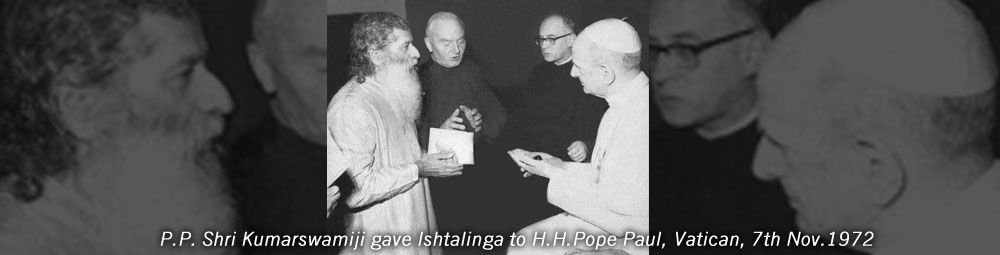

This article – Mysticism of Sharanas I – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Virashaiva Philosophy and Mysticism’.