Literature is an art and the heart of art is beauty. Art is creative but its creativeness lies in expressiveness. Expressiveness has degrees; it varies according to the fineness of creative inspiration and the plasticity of the instrument of expression. If the inspiration can express itself with case and freedom, it becomes finally artistic. But inspiration can be received from different strata of being; hence artistic creations differ in their impressions. Inspirations may be received from vital nature or from the still finer planes of consciousness. .

The task of the sage is to express the supreme word in life, the task of the poet is to express the word in speech. Basava undertook this double task and carried it to a successful termination. In giving an artistic appreciation of the sayings of Basava, we observe that Basava is copious in his coinage of new expressions, striking metaphors, witty concepts and novel terms of thought. He has a clear yet devout eye which always searches into the heart of things; an enlightened mind which aspires after more light; a keen understanding which finds the scholastic expressions insufficient to express the infinite.

Kannada belongs to the Dravidian group of languages which comprises Tamil, Kannada, Telugu and Malayalam, besides dialects like Tulu, Kodagu and Gondi. The literature of Kannada is of far greater antiquity than that of any other south Indian language except perhaps Tamil. Kannada literature is roughly classed as Jaina, Veershaiva and Brahmana; this classification, though convenient, is clearly arbitrary because artistic sensitiveness defies any such division, The earliest cultivators of the Kannada language were the Jains who carried this cultivation up to the 12th century. About three centuries after that period, there were a few Brahmin writers and pretty large number of Veershaiva authours, and from the 15th century Brahmanical and Veershaiva works are seen in abundance. The dominant feature of the Jain works is that they are Champu Kabyas or poems in a variety of composite meters with sprinkling of paragraphs in prose. The earlier Veershaiva works are mostly in the form of Vachanas or poetical prose, and occasionally in the Ragale and Tripadi meters. The Vachanas are written in simple lucid and forceful style with the object of propagating religious and philosophical truths. After the Vachana Sahitya comes the Dasa Sahitya which is characterized by emotional sensibility and exquisite music. The recent compositions are mostly in the form of Yakshaganas or rudimentary dramas which are interspersed with songs while some are in prose only. In the 19th century, a great impetus was given to the advancement of Kannada literature by the Mysore Kings. With the beginning of the 20th century begins an entirely new period of Kannada literature, consequent upon the English education in India, the impact of European civilization and the introduction of Western scientific methods of research. Literature, whether ancient, mediaeval or modern, has the same purpose and the same function, in spite of the differing garbs which it is obliged to wear in accordance with the needs of the environments.

In enumerating some of the characteristics of Kannada literature, E.P.Rice remarks thus: “I am afraid it must be confessed that Kanarese writers, highly skillful though they are in the manipulation of their language, and very pleasing to listen to in original, have as yet contributed extremely little to do the stock of the world’s knowledge and inspiration. “Well, what is literature? Why does the writer create it? Why does the reader read it? From where does come the urge to write a beautiful poem, a drama or a story? The universe where man lives presents him with two aspects – one the Truth and the other Beauty. The faculty which helps man to realize the aspect of truth is reason, whereas the faculty which incites him to enjoy the aspect of beauty is imagination. In each one of us there is Prajna and Pratibha, however veiled its workings may be. Each one of us reacts to his surroundings intellectually as well as emotionally. If reason reveals the majesty of truth, creative imagination discovers the beauty that surrounds it. The function of literature is to discover this beauty and to communicate it to readers. To grasp the hidden beauty in whatever is seen, heard or experienced, and to express so as to convey it to others is the insistent urge that leads to the creation of literature. The common man does not feel the joys and sorrows to their full measure and also he lacks the power to give expression to what little he feels. But the literalist, whatever he may be a poet, a novelist or a play-writer, can by the power of sympathy, enter into his feelings and express them beautifully. At the touch of the literary artist even a sad experience turns into a thing of beauty. The literary artist is therefore a man who possesses an uncommon emotional sensibility, and an uncommon power of imparting his own emotional exuberance to the readers. The literary artist is therefore a man who possesses an uncommon emotional sensibility, and an uncommon power of imparting his own emotional exuberance to the readers. “The intensity, quickness and subtlety of emotion and the power to express an emotional experience in beautiful words – these are the essential virtues of the literary artist. They are the true test of his goodness and greatness. And therefore, they are also the only test of the quality of all literature. A novelist is great not because he champions a social, religious or political cause, but because his writing bears the hall-mark of his emotional depth and intensity and also of his power to convey to the reader his own emotional exuberance. All other tests are evidently extraneous and irrelevant.” If the above mentioned virtues are present in Kannada literature, it shall have served the purpose. Since they are intimately present in Kannada literature it finds a respectable place among the literatures of the world. The contribution of any literature, if there is any contribution at all, lies in its affording the delight of a deep emotional mood.

If the function of literature is to discover beauty and communicate it, what then is beauty? Beauty is essentially expression which must be concrete, rhythmic and harmonious. It is the expression of delight in the harmony of life and in the music of soul. Delight is beauty and delight as beauty is concrete and dynamic in its expression. Hence beauty is associated with they dynamism of life and spirit. It frees the soul from the touch of matter and introduces it into spirit. In this exalted height of existence the soul feels a new attraction, a new delight in the wide expression of spirit, not through nature but through itself. And freedom from nature’s touch impresses it with the absorbing sense of fresh delight, exquisite harmony and supple expression. Aesthetics or artistic contemplation emancipates the intellect from the demands of will, for beauty is to art the soul’s attraction and the eye’s rest. This contemplation elevates the soul from the working of the sense and seals the union of love in complete absorption. But he enjoyment of beauty is not possible unless the beauteous object is concrete.

Literature is an art and the heart of art is beauty. Art is creative but its creativeness lies in expressiveness. Expressiveness has degrees; it varies according to the fineness of creative inspiration and the plasticity of the instrument of expression. If the inspiration can express itself with case and freedom, it becomes finally artistic. But inspiration can be received from different strata of being; hence artistic creations differ in their impressions. Inspirations may be received from vital nature or from the still finer planes of consciousness. They will give us different forms of creation, some will affect directly our vital mind and some will produce deep currents of the soul. The value of art will depend upon the kind of rhythm and harmony it produces in our psychic being. Every artistic creation gives us delight, for that is the soul or art. But its artistic fineness and inspiration will mainly depend upon the part of being if affects, and the kind of response it elicits. The vital emotion, the pensive mood, the finer delight, the sense of spiritual case is a few among the various shades of the effects of art upon our mind, but all of them have not the same value. Artistic inspiration should not be guided by an standard other than the intensity of expressiveness and the kind of feeling it generates.

Vachana literature is an art, but it is a genuine art in the sense that it enters into the recesses of soul and reproduces the finer ideas and harmonies sleeping in its bosom. There is melody and music of life in the inmost existence of our being; and the Vachana literature has produced the fine creation because it has had the capacity to catch inspiration there from. Realistic reproduction with the touch of nature may appeal to the vital mind, but it does not answer the soul’s craving. Life is music and harmony and in no phase of it can these be absent. To understand and enjoy life it is necessary to possess artistic sensitiveness. Many are not responsive to the music of the soul, many are not responsive to the deeper tones in music which makes us more and more alert and self-conscious. Vachana literature makes us responsive to the music of the soul, and awakens finer shades of feeling in the depth of the soul. Genuine art is expressive of the finer attitudes of the soul such as beauty, power, holiness and dignity. It is the privilege of art to seize upon the deeper layers of Being enfolded in the soul and to give expression to them. And in the height of our being art comes to possess a religious character, for it represents a form of divine inspiration. Hence genuine art originates from religious or spiritual consciousness, and Vachana literature is representative of this genuine art which makes it sublime.

Basava and Chennabasava.

If beauty is predominant in Dasa Sahitya, sublimity is predominant in Sharana Sahitya. If one presents beauty of Krishna’s Rasa dance, the other presents sublimity of Shiva’s Tandavan dance. Both of them are equally artistic. The one moves the heart in radiant feelings and rosy colours; the other, the movement of heart and hushes our whole being to encounter a transcendent experience. Beauty does not always lie in the gentler movements of life, it also lies in the more strenuous movements. There is beauty in the rugged mountain, there is beauty in the dance of destruction, there is beauty in stark nature, and there is beauty in the fierce and the terrible. If the human soul can forgo its usual weakness, timidity and love of the agreeable, it can see and feel the more majestic harmony of nature revealed in her ruggedness, fierceness and destruction. This harmony is supra-vital and upsets the vital expectations, but the supra-vital and the supra-mental are expressed in such sublimities. There is the silent music in discord and the finer harmony in conflict.

All the great prophets evince an extreme sensitiveness to one or more aspects of beauty. They are all characterized by a fine imagination, and one wonders at their nearness to nature in all their discourses. The world knows of Buddha as a great philosopher but he was poet as well. He stated his teachings in verse in order to make them easily remembered by the people. When we consider the sermons of Christ, we find how near he is to nature and what a delicate sense he has for nature’s beauty. Similarly Basava’s sayings abound in similes and metaphors drawn from nature. The more purified and lofty is a man’s character, the more sensitive he becomes to the hidden beauty of divine manifestation. It was Ruskin who insisted on the need of artistic sensitiveness as a qualification for a perfect character. When our mental horizon becomes wide and responsive to the inner secrets of nature, every thing in life exhibits beauty. It is true that we see the unbeautiful on all sides; the unholy and the impure challenge our belief in beauty. But unloveliness or ugliness is not the essence of the world but only its accident, as is a discord in music. In a universe which is pressing forward to perfection, unloveliness in men and things is but a transition. The understanding of man and the recognition of purpose in evolution quickens the artist’s sensitiveness to the hidden play of the forces of the beautiful.

Many discussions have taken place in trying to define the significance of classical and Romantic art. There is duality which constantly haunts us in everything in life. Art expresses this duality as life and form. If classical art deals more with form, romantic art is concerned with life. Classicism tries to be true to external nature and attempts to depict the thing seen by the outer sense, while Romanticism is nearer to the internal nature with an attempt to contemplate the rhythm of beauty through inner sense. The essential notion of classicism is that it is a Formative Activity, and that of romanticism is spontaneous activity. The psychological impulses, self-adjustment and self-identification, when they are applied to the literary art, assume the forms of classicism and romanticism. These two impulses are ever present in human nature, and they manifest themselves as objective and subjective approaches to reality in all literature. In European literary history, the French revolution gave a great fillip to the Romantic Movement. By the end of the 18th century life stirred anew in men’s hearts. The Romantic Movement was in some way a complete break with the then dominant classical art and literary standards. It has been said that the rules evolved from classical tradition were not suited to romantic ideals; the former aimed at symmetry of outline and perfection of form, whereas the latter aimed at the expression of individuality. The Romantic Movement therefore tended to discard formal beauty in favour of emotional intensity. Heine, the German poet, said that, “classical are had to express only the finite, and its forms could be identical with the artist’s idea; romantic art had to represent or rather typify the infinite and the spiritual, and had therefore to be expressed symbolically.”

Spontaneity is the only word which brings out the significance of romanticism. Basava was spontaneous, that was his distinction and originality. He became a writer by instinct being provoked to compose sayings. He continued to write his sayings free from technical rules. The result was a style which is peculiar to romantic prose – the interior monologue. The monologue is sometimes confessional or confidential, sometimes suggestive or symbolical. Basava’s sayings are therefore the poetic – prose of the interior monologue, the whispered secrets of the self. There had been much introspective writing prior to Basava. If we examine those works we find that they are all governed by the rules of rhetoric, together with an objective approach. But in a work of monologic literature like the Vachanas we are in contact with a state of pure subjectivity. It is this subjectivity that expresses the depths within the self that represents true inwardness. Reason itself is found to be part of that true inwardness; because the heart has its own reason which reason does not know. But the subjectivity which is thus postulated as the standard of Truth is not narrowly individual subjectivism, but it is universal in the sense that it recognizes the self of others too. One may object to this by saying that this is existentialism; yes, existentialism is romanticism par excellence, in other words, it is the philosophical aspect of romanticism. D.H.Lawrence wrote: “One realm we have never conquered, the pure present. One great mystery of time is terra incognita to us, the instant. The most superb mystery we have hardly recognized, the immediate, instant self. The quick of all time is the instant. The quick of all universe, of all creation is the incarnate self.” One cannot claim that the subjective prose or poetry of the Vachana literature is necessarily greater than the objective poetry of Pampa, Ranna, Ponna etc; but he does claim that it is a different kind of literature. And he is fairly confident that it has widened the sphere of human sensibility, and to have done that, as Wordsworth said, is the only infallible sign of genius in the fine arts. It is a strange thing that men do not understand that life is the great reality, that true living fills us with vivid life. The Vachana literature bids us to live the life fully and heartily.

India’s Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh released coins commemorating Basava.

Aesthetics is a normative science which deals not with mere facts of experience, but with values. It investigates the meaning of aesthetic pleasure, the subjective as well as objective character of beauty, the origin and nature of art impulse. The peculiar characteristic of aesthetic pleasure is that it is disinterested. This marks it off from all other pleasures which have an element of desire involving personal or vital interests. Sugar is not beautiful, it is agreeable; we have to possess it in order to enjoy it. But the beautiful is always the object of disinterested satisfaction. Beauty, although it is mental, is objective since it is the object of a judgment, which regards beauty as a quality of objects. Plato in his Dialogues seems to hold an objective theory of beauty. It is, as if it were, a reality in itself, a kind of eternal and unchanging essence, any individual beautiful object being said to participate in this essential beauty. Sometimes he speaks of harmony, proportion and symmetry as constituting beauty; still he thinks of them metaphysically as objective qualities of things. According to him, even mathematics rightly viewed possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty, a beauty cold and austere, yet sublimely pure and capable of a stern perfection such as only the great art can show. Plotinus also thinks that beauty is the pure effulgence of divine reason. When the Absolute shines forth in pristine reality, it is beauty. The artist is the seer who can see the divine beauty. To Hegel also beauty is a kind of disclosure of spirit. Beauty is the absolute idea shining through some concrete medium. To Schopenhauer beauty is the absolute will objectifying itself through types. Anything is beautiful in proportion as it realizes or approximates to the type. In moments of pure contemplation when we deny the will-to-live, we are able to see this ideal beauty. Ruskin also believes that beauty in objects is found in certain qualities such as unity, repose, symmetry, purity, and moderation which typify divine attributes. William Knight, in his book, The Philosophy of the Beautiful, sums up the objective theory thus: “The art products of the world register the insight of the human race into beauty, and the nations of the world have left their profoundest intuitions and ideas thus embodied. Art gives to phenomenal appearances ‘a reality that is born of mind’, and through art they become, not semblances but higher realities. It is thus that art breaks as it were, through the shell and gets out the kernel for us.”

This objective theory has brought into bold relief the beautiful aspect of the divine. The Absolute is not only Good but it is also beautiful, but this beauty is realized more in the depths within than in the vastness without. This is the claim of Romanticism. It has always recognized intuition as the impelling force in art. Be it noted that there are levels of intuition such as philosophic, mystic and artistic. The intuition which romanticism has recognized is a sort of na�ve intuition. This simple but unobtrusive faculty was vaguely understood by Homer and Hesiod when they said that their songs were god-inspired. Artists often speak of their inspiration; they look upon themselves more or less as mere instruments of something or some power that is beyond. The great artists are precisely those in whom the instrumental faculties offer the least resistance, and record with absolute fidelity the experiences of the Beyond. About the close of the 18th century intuition became the basis of romantic creed. Blake distrusted all other faculties in verse making except the intuition. He literally believed that his verses were the work of a power superior to himself. He leaped straight into the ill-logical, the irrational and clothed his poetry in a strong symbolism. Wordsworth’s conception of poetry was that of powerful psychic flame welling up from the dim depths of soul. To him every object had a double significance – one for the superficial self and the other for the subliminal. As a poet he realized the latter significance to prolong the thrill of life. To Shelley the poetry was a fine essence exhaled by the human mind in a state of rapture. Poetry was to Coleridge the union of deep feeling and profound thought. Walther Peter considered art to be a method of translating thought into expression. Oscar Wilde seized on this idea and turned it into a pleas for the doctrine of Art for Art’s sake. Croce denied this function to art, he assigned to it the role of purely affective-ideational character. Abhinava Gupta anticipates Croce in his expressionist theory of beauty but he differs from Croce in identifying beauty completely with expression. He accepts the feeling element in beauty, otherwise there would be no difference between a pure expression and a beauteous expression. Abhinava Gupta is nearer to mysticism.

The literary artist or the musical composer is impelled by some insistent prompting to create something beautiful. The activity is spontaneous; it is a kind of overflowing. But there is also a social element in art, which is its significant part. The potential artist, with his profound emotion or his great thought or his new vision, not only desires to give adequate expression to his mental state, but he demands the sympathetic expression and experience of his fellow beings. The closest bonds of sympathy unite the members of a group. Each one shares the joys and sorrows of the others, and each one wants others to share his own newly found joy. Because of this reciprocity the art impulse has been called the pursuit of social resonance. The artist gains an actual sympathetic response from his fellows, his own emotion being enhanced by this social diffusion. The art impulse is thus a kind of extension or enlargement of one’s personality. It is a social enlargement, the instinctive need to have others think and feel with us. The artist’s audience is therefore not limited to his circle of friends, but extends to another world and to posterity.

This principle of social resonance explains the difficulty about the relation of aesthetics to ethics. Are there moral lessons in works of art? Does the artist aim to instruct or to edify? The artist is not a teacher nor a preacher. He is just a sharer. He has a divine thought, a profound emotion, and his only wish is to share it with one and all. In this capacity the status of the artist is higher than that of the teacher or preacher. The true artist, in representing the free elastic life, naturally has an advantage over the moralist and commands a wider outlook than his. But it must be remembered that the perception of his elasticity is relative to the fineness and transparence of being which is associated with the ethical responsiveness and purity of being. Hence it follows that art is a great moral influence, it is the expression of our spiritual ideals and the power of the artist for good is without limit. Greek art was distinctly moral, it carried a great lesson but never in the form of a lesson. Finally it is in the imaginative work of the artist that the creative power of the human mind attains its perfection. And this power is seen at its best in the fine arts, where even the beauties of nature are surpassed. In his striving after life, full and free, the individual finds the environment sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile, But art supplies an environment from which strife, foreignness, obstruction are eliminated. It actualizes the unity, spirituality in the environment; it frees and enhances the life of the self to the environment which art successfully creates; the mind finds itself completely and harmoniously adapted by the initial act of perception. In the world of art, value and existence are one. This is pure mysticism.

Basava was a mystic and his sayings bespeak of his mystic fervour. The mystic is essentially a seer. His art is to discover the secrets of God and proclaim them to men, to read the book of Nature and interpret it for us. Francis Thomson observes, “The mission of a mystical poet is to bring home to our earthly and finite minds supernatural and infinite truths, he has to translate for us the things of the spirit by the things of sense; he has to give the supernatural as many points of contact as possible with the natural; he has to enable us to apprehend by means of material symbols those spiritual realities which transcend human experience.” The task of the sage is to express the supreme word in life, the task of the poet is to express the word in speech. Basava undertook this double task and carried it to a successful termination. In giving an artistic appreciation of the sayings of Basava, we observe that Basava is copious in his coinage of new expressions, striking metaphors, witty concepts and novel terms of thought. He has a clear yet devout eye which always searches into the heart of things; an enlightened mind which aspires after more light; a keen understanding which finds the scholastic expressions insufficient to express the infinite. Deep feeling and love for the truth are united in him with a lively and real fancy, which enables him to make the clearness of his thought, becomes evident in his art. He wrote little but his writings may be regarded as the quintessence of mysticism.

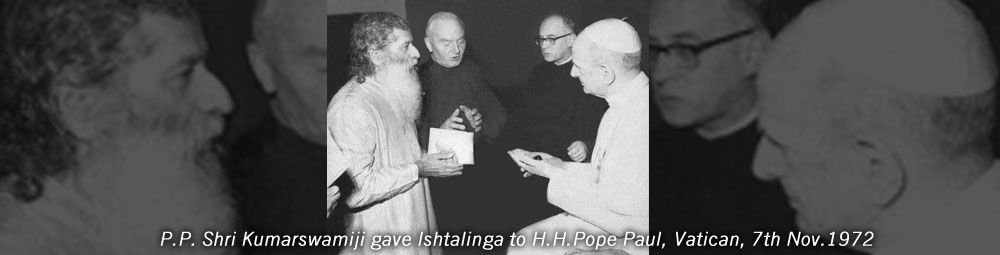

This article – Basava and Kannada Literature- is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Buddha and Basava’.