Basava was an ardent of Kudala Sangama – his Ishta-devata. As an arta bhakta, he had a gift of inner vision by virtue of which he recognized that behind natural things there lay a unity. The mysticism preached by Basava embodies a sublime theism. God is the great transcendent Being who creates and preserves all the worlds. Countless are His attributes; peerless are His dealings, priceless are His gifts. In this sublime vision of God, the reader of his sayings will hardly fail to notice the swift and exquisite touches of eager and tender love, sober ethics and sublime thoughts.

Basava was a mystic by temperament. His sayings are the outpourings, prayers and appeals to the Divine. They reveal a heightened intensity of love which Basava had cherished for God. He had pivoted his life on Love Divine. “Love is the one supreme duty and good, that love is wisdom, purity and valor and peace and that its infinite sorrows is infinity better than the world’s richest joy.” It was such love that filled the heart of Basava and possessed him. It was again this love that guided and governed every action and thought of Basava. His whole mission was based on the highest levels of spiritual life. Mysticism is the art of union with God through love. This union, which is intuitive and ecstatic, is obtained by contemplation. Visions of such contemplation abound in his sayings. It is in the fitness of things that the sayings begin with an account of a vision of Basava’s seven births, just as the book of the prophet Isaiah starts with the description of the mystic vision in which Isaiah is consecrated to his vocation.

Basava was truly a religious and righteous man. Religious experience implies a joyous feeling that there is a being infinitely better than ourselves and that our life and destiny are dependent upon Him. “If this immediate reality of the higher principle be taken away there would be nothing left of religious experience. It would no longer exist. But it does exist; consequently that which is given and experienced in it also exists. God is in us, therefore He is. “Basava’s whole outlook on life was based on the attainment of God-realization, this he sought through integral fullness of life. His quest was not influenced by the ‘will-lessness’ of the ascetic renouncing all life but was broad based on the formation of the perfect Man or Sharana who does not forsake the world for Nirvanic rest or feed solely on the realm of ideas, but enters on the path of the world mostly to save and if possible to turn it into the kingdom of God.

Basava was an ardent of Kudala Sangama – his Ishta-devata. As an arta bhakta, he had a gift of inner vision by virtue of which he recognized that behind natural things there lay a unity. He had cherished a living faith in the goodness of God and his mind was filled with aspirations of a joyful soul, conscious of its kinship with God. These are clearly the characteristics of mysticism and Basava was a mystic in the true sense of the word. Giovanner Papini in his book, ‘A Man Finished’ states thus: “Mysticism, in fact is but the overthrowing of barriers, the negation of detachment, an impulse towards the absolute and eternal inseparability. The mystic does not feel himself separated from the world, from the universe and from God. Therefore, having become an intimate and integral part of the world, all that remains of his will is reflected in the universal, having surrendered his own personal will, he unconsciously becomes a species of universal will and the physicists most stringent laws must collapse before the amorous desire of the ecstatic.”

In the sayings of Basava, there is a great deal of Veerashaiva theology as well as much of Hindu mythology. Yet nothing could be simpler than the to abstract philosophic theory of life and to discover the secrets of God which they express. It is, rather, when we read his sayings between the lines, the sayings which are noted for their simplicity and beauty that we derive the benefit from them. Since the sayings are redolent of theology and mythology, they unmistakably contain an element of religion – religion understood both in the sense; in the primary as well as secondarily. Religion is primarily a quality of life, only secondarily, it is concerned with beliefs, forms dogmas and ceremonies. It is in this secondary sense that the term religion is commonly understood. But the truly religious man is he who manifests the spiritual quality in his life, whatever may be his personal religious belief. What we expect from the religious man are righteousness, virtue, love and charity, and religion as a quality of life produces these in him. In Basava, we find these qualities in abundance, though he traditionally belongs to the Veerashaiva fold.

In his sayings, we meet Basava first as a religious man and then as a mystic. Of course, there is no hard and fast line of demarcation between religion and mysticism, the whole of religion is in a sense mystical, though it is not mysticism. Mysticism is more or less a definite realization of what in ordinary religion is a firmly discerned far off possibility. In religion, there is a relation, the lower and higher selves are still separated, whereas in mysticism there is identity. Religion is the first stage of the mystic way, since there is a relation, one of its principal elements is worship. This worship must necessarily assume a great variety of individual forms according to the intelligence of the worshipper. First of all, Basava was a monotheist and he worshipped God in the form of Linga.

“A trusted wife but signified

A single lordship. The devout too

Who knows of trust have it in one.

Beware! Another God is treachery

Forbear! Another God is adultery

And pays the toll of the culprit’s nose

If Kudala Sangama chances to see.”

Basava demands that there should be harmony between words and deeds in the worship of God.

“Let the words be like the pearls on a string;

Let the deeds be in tune with words

How else can Kudala Sangama be pleased?”

The tongue praising God without the heart is but a tinkling symbol; the heart seeking God without the tongue is still music. Both in concrete make their harmony which fills and delights both body and mind. This concrete, this harmony is found in the mode of worship which Basava brought into vogue. For the mode of worship corresponds to the essence of God which is spiritual and the feeling of the worshipper corresponds to the character of God which is filial. In the divine relations which Basava had established towards God, the filial tie was predominant. Basava visualized three aspects of God. The individuals, the immanent and the transcendent. In the initial stage he comprehends God as a creator distinct from all created things. “Though all spring from God, can they be God? The farmer sows the seeds; can the crop be a farmer? The potter makes a pot, can the pot be a potmaker? God is here regarded as an object of worship and adoration and the distinction is made between Creator and creature. In the next stage, he visualizes God as the indweller or the indwelling Spirit pervading every thing like the flavour of a fruit, scent of a flower. The very first saying of Basava makes this point perfectly clear.

“Like the fire immanent in the deeps

Like the sweetness in the nectar of the moon,

Like the fragrance in the bud,

And, Oh! Kudala Sangama,

Like a maiden’s love is it –

The unnameable in Man.:”

Finally, he realizes God as pure Existence, as the transcendent Reality which is termed Bayalu, Nirbayalu, Shunya, Nisshunya in Veerashaivism. Be it noted that Bayalu or Shunya means neither void nor space. It means pure Existence which is the negation of all countrardictions (counter-indications?) and dualities and which transcends all relation, all processes and all formation of words. His saying is clear and emphatic on this point:

“The all-Knowing Veda took fright at the Linga,

Wherein Knowledge knows not what it is.

The Shastra despaired of attaining Linga,

Where attainment is not what it vaunts.

The Science of Logic that thrashes much beside

And around, linga well alone

The vistas envisaged by Agamas showed

How impossible near is Linga

For, angels and men, help not missing what

Kudala Sangama’s servants must measure.”

And again,

“All mystic names that signalizes Linga

Are charms to conjure shadows

Of distant something Else.

The Linga ever is in spite of

Every name and form.

The Linga never owns but

Chisels figures in the flesh.

Beyond and far above the Great

Almighty stays with Linga

And every flight to Him must

End in Kudala Sanga’s Being.”

Mysticism, like religion, has many phases of experience and many degrees of attainment. It begins in intuition and ends with the realization or the mystic experience of the Infinite. The remarkable thing is that an invariable sense of unity or wholeness always accompanies the mystic experience. The last but lofty saying of Basava brings into bold relief the truth of this statement.

“The self in contact is the same

From this end or from that, Oh! Man,

The mystic whistle, glare and trance

Are tokens of the supreme Linga

Transcending and preserving all

But Kudala Sangamdeva knows

And He alone, the rapture-spell

In which both Man and God are one.”

The mystic experience affords a strong support and argument for that intuitive philosophical sense of unity which finds its expression in monistic systems, when man has once clearly realized that there is nothing in the universe which is really separate, that everything if pushed logically to its ultimate conclusion, would expand to infinity and become the Absolute, that every atom is balanced against the whole universe and acts and reacts at every moment with the whole and that the whole is present at every moment and in everything, he has then gone a long way towards an understanding of the true nature of mysticism. Of the true nature of mysticism, which implies a unitary consciousness, William James speaks eloquently. “This overcoming of all the usual barriers between the individual and the Absolute is the great mystic achievement. In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness. This is the everlasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime and creed. In Hinduism, in Neo-Platonism, in Sufism, in Christian mysticism, in Whitmanism, we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think and which brings it about that the mystical classics have, as has been said, neither birthday nor native land. Perpetually telling of the unity of man with God, their speech antidates languages and they do not grow old.”

The mystic achieves the realization of the Infinite more through love than through anything – the love which knows no bargain, which knows no fear and which is its own ideal. The pure, fearless and self-less love is both the method and the goal of a mystic. At all stages and in all degrees preeminently it is love that determines and governs all his efforts and aspirations, his joys and sorrows, his attainments and failures. None has ever experienced the bliss of love to the same degree as the mystic and none ever can suffer as the mystic has suffered when the response of the Infinite appears to cease or seems to be held in abeyance. The following sayings of Basava reveal the agony, the suffering or the pangs of separation:

“I am caught in life entanglement;

And I cry out “Help, Oh!, Help”

But all is null and void.

Lord Kudala Sangama,

I cry for mercy.”

“Like the moon I was

Under the spell of phases

The Rahu of mundane life

Has finished me completely

By his darkening gulp

Now is my body in full eclipse

When I can expect deliverance Oh! Lord,

Kudala Sangama?

Oh! When?

When will my life’s thankless servitude end?

When will it attain fruition in my mind –

When will it, of Kudala Sangama

When shall I be in bliss Supreme.”

The abiding interest of mysticism lies in its affirmation of the claims of the human heart and in the moral and spiritual uplift to which it has given a stimulus. Basava surrendered himself to the ideal of love which has been “the anchor of pure thoughts, the guardian of the heart and the soul of moral being.” Fichte said, “Man can will nothing but what he loves, his love is the sole and at the same time the infallible suffering of his volition and of all his life’s striving and movement.” If this is true then we can, without any fear of contradiction say that love is revelation in knowledge, inspiration in art, motive in mortality and the fullness of religious joy.

Evelyn Underhill speaking of Kabir generalizes the theme of love: “Love is throughout the mystic’s absolute Lord: the unique source of the more abundant life which he enjoys and the common factor which unites the finite and the infinite worlds. All is soaked in love, that love which he described in almost Johannine language as the “Form of God”. The whole of creation is the play of the Eternal Lover; the living, changing, growing expression of Brahma’s love and joy. As these twin passions preside over the generation of human life, so he finds them governing the creative acts of God, His manifestation is love; his activity is joy. Creation springs from one glad act of affirmation; the everlasting yea, perpetually uttered within the depth of the Divine Nature. In accordance with the concept of the universe as a Love Game which eternally goes forward, a progressive manifestation of Brahma. Movement rhythm, perpetual change forms an integral parts of mystics vision of reality.”

Socrates and Fitche. told us that to know self was to know nature but Basava told us that to know nature was to know self and know self was to know God, for God is immanent both in man and nature. Coleridge in his ‘Religious Musings’ echoes this idea”

“It is the sublime of man

Over moon-tide majesty to know ourselves

Parts and portions of one

Wonderous whole!

But it is God

Diffused through all, that doth

Make all one whole.”

‘Die to thyself that thou mayest live’ this formula rang in Basava’s heart as a constant refrain. He made incessant efforts to establish a direct relation to God, so that his ever repeated call for Dasoha indicated nothing but an approach to the Divine Reality. His philosophy of life cannot be summarized better than in the words of Dr. Carpenter: “god is through all in all, so that life and time are His through all in all, so that he breathes in our breath, speaks in our speech, thinks in our thought. What then shall we suffer and He knows not? Are we in pain and will He not feel? It is the mystery of His nature to be the Eternal and the All pervading and yet to blend Himself with our moral frame and to abide unchanged while we grow and decay.”

Mysticism has many degrees of attainment which present themselves as stages on the mystic way. The classical literature of mysticism admits broadly three stages – the stage of purification, the stage of illumination and the stage of unification. Such a division is useful in many respects, though each stage necessarily shades off and is illumined by the higher one. But Veerashaivism further makes a two-fold division in each stage and thus it reckons a six-fold division or rather six stages on the mystic way. This six-fold division is by no means a arbitrary one, rather it gives us a better proof of the psychological analysis of spiritual experience. These six stages, which imply the spirito-psychological hierarchy, goes by the name of Sat-sthala in Veerashaivism. They are Bhakta-sthala, Mahesha sthala, Prasadi-stahala, Pranalingi-sthala, Sharana-sthala, Aikya-sthala. The sayings of Basava are arranged according to the technique of Sat-sthala.

The first stage is known as Bhakta-sthala where a moral purification plays an important role. The moral purification of the lower self or chitta-shuddhi, free from attachments to the things of sense, from evil passions and desires and, begins to come in the offing. Here the purification of self-will is accomplished. The purification which is difficult to accomplish, since it has behind it the whole accumulated force of the previous outgoing existence of the individual. In the second stage which is known as Mahesh-sthala the purification of the intellect takes place. Training of conscience is a feature of this stage and the trained conscience reveals itself as integrity. Mahesha, is, therefore, a man of integrity who will never listen to any plea against conscience. Integrity is the first step to illumination, to maintain it at all times costs self denial.

The third stage which is known as Prasadi-sthala begins with the dawn of Intuition, which arises out of an intellectual purification of those formal concepts which are the deposited sediment of intuition. In the Prasadi-sthala there is a definite mental attitude in which one is seen in the many and the many in the one. In the fourth stage known as Pranalingi-sthala the intuition ripens into illumination and gives to the Pranalingi a foretaste of the cosmic consciousness. Dr. Bucke in his Cosmic Consciousness gives many an example of similar nature some of which are of religious character. The plane of cosmic consciousness is in Indian yoga philosophy the typal or causal plane termed karana-sristi. It is sometimes known as the Archetypal world or the world of Ideas, the plane of Logos, the perfect land of religion in which the subtle forms of all created things are held to exist. Profesor Max Muller tells us in his psychological Religion thus: “The Logos, the word, at the thought of God as the whole body of divine or eternal ideas, which Plato had prophesized, which Aristotle had criticized in vain, which the neo-platonists re-established, is a truth that forms or ought to form, the foundation of all philosophy.” Yes, of all philosophy as also of true mysticism, the true mystic or the Pranalingi lives, moves and has his being in the world of Ideas, to him it is the real world and this phenomenal world is only a derivation.

The fifth stage which is known as Sharana-sthala is characterized by ecstasy. The ecstatic state which the Sharana countenances is not passive but active. He does not approve of that ecstatic state in which the subject is wrapped away into total unconsciousness of both bodily and mental activities. To him the real ecstatic state is the state of unspeakable bliss which the individual enjoys while he is yet working. The ecstatic life of the Sharana may be described as the life of a divine and happy man, as a liberation from all worldly cares and concerns and as life unaccompanied with human pleasures. The sixth stage which is known as Aikya-sthala is really the stage of union with the Absolute or God. How can union with God be described: It is not seeing but meeting and fusing with Awareness. The soul is imbued with a life of incredible intensity and passes into a state which defies all description. The only criterion is to remain silent. Yet the mystic essays to articulate to his unitive experience. Basava who had attained this state, exclaimed thus:

“Arrayed in blazing splendours unsurpassed,

Supreme, sublime and vast, the “I” held sway.

Sooner than I could say my tongue was mute

A wonder wrapped up in the luminous Dawn

Oh! Kudala Sangama’s Day, saw me awake.”

Here, the wheel of life has completed its circle. Here, the extremes of sublimity and simplicity are seen to meet. Here, the final consummation of the soul, journeying through periods of alternative stress and glory, leading ever to greater transcendence coming ever in closer contact with the Absolute, has been achieved. It has been customary with nature-poets “to make nature the eternal reality of beauty in the super-sensual world of thought.” It was Keats who wrote: “the roaring of the wind is my wife and the stars through the window are my children.” Symonds said in the case of Shelley, “The absorption of the human soul into primeval nature forces, the blending of the principle of thought with the universal spirit of beauty is not enough to satisfy man’s yearning after immortality. It is only the Indian thought or the Upanishadic seer who proclaimed thus: “The whole world is born of Ananda, lives in Ananda and wheels from Ananda to Ananda. Every soul is therefore potentially mystic. To intuit, to experience, to realize this state of Bliss or Ananda is the mystic’s magnum opus. All mystics speak of a faculty which, when it begins to function, has the reality of bliss brought within the ambitious of consciousness. This is called the mystic sense and Basava had this mystic sense in abundance.

The mystic is a fortiori the religinis, the saint whose love flows from devotion to God. His standpoint is the standpoint of universal love and the changes that happen in this Lover or in the ecstatic state of the mystic are described in all works on mysticism and similarly in the sayings of Basava. In the ecstatic mood, tears stream down from the eyes of the mystic; joy thrill in all the pores of his body; he is obsessed by the contemplation of the divine excellence or the supernatural glory. Such supernatural glory is amenable only to the mystic sense. The materialist with his five senses seeks to discover only five modes of motion in nature. To conclude from number five of the senses to the number five of modes of motion is a logically fatal step. For the number of forces prevailing in Nature is legion. Carb Du Prel in his Philosophy of Mysticism makes a pertinent remark: “The denial in principle of a super-sensuous world is thereby definitely set aside. Therefore did Protagoras add to his judgment that man is the measure of all things, the weighty words of things that are not.” The human senses change, forthwith there is a quite different world; our senses multiply; forthwith will nature appear far richer.”

Basava bases the authority and source of faith in the heart of man – its intuitions and longings. He, therefore, lays great stress on individual revelation. This kind of personal revelation is somewhat different from the Upanishadic revelation, which says that God making his own choice. But personal revelation says that God adapts himself to the mystic’s choice; this is a profounder truth in the world of mysticism than God choosing his own choice. The intimate fact for a mystic is immediate experience which reveals the existence of the Indwelling Spirit, the Light that lighteth every man. Revelations through scriptures are but justification of this immediate experience. Against this background, one may visualize the concept of Sharana as adumbrated by Basava. Sharana is a realized soul or rather he is one to whom God has revealed himself according to the intensity of his immediate and inner experience. Jangamas or Sharanas were the living example of individual revelation. Basava looked upon them as the living embodiments of God’s presence. Often times he insisted upon his followers to seek the presence of God no where else but in them. If man is known by the company he keeps, then it is better for him to be in the company of the holy ones or the realized souls for Basava says:

“If tree with tree embrace and chafe,

Will not ignition set them ablaze?

Will not the touch of High souled men

Enkindle knowledge and burn up

The grosser tendencies of Man?

It will, Oh! Kudala Sangamadeva

I pray, lead me to pure souled Men.”

The mysticism preached by Basava embodies a sublime theism. God is the great transcendent Being who creates and preserves all the worlds. Countless are His attributes; peerless are His dealings, priceless are His gifts. In this sublime vision of God, the reader of his sayings will hardly fail to notice the swift and exquisite touches of eager and tender love, sober ethics and sublime thoughts.

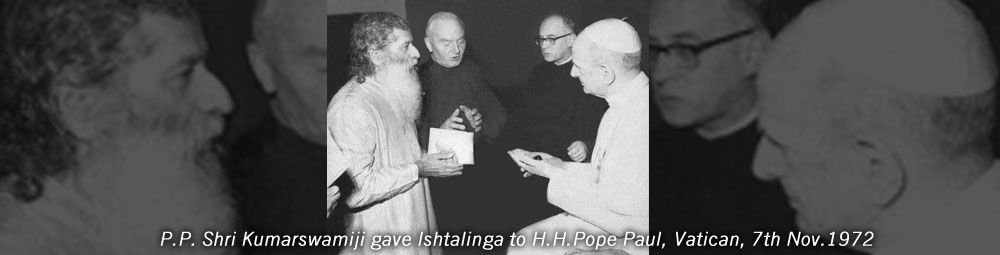

This article is taken from H.H.Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Veerashaivism: Comparative Study of Allama Prabhu,

Basava,Shunya-Sampadane and Vachana Shastra’.