Throughout the sayings of Prabhu are discernible the sparks and signs of a powerful mind, emancipated from the influence of authority, and devoted to the search of the eternal truth through poesy. The melody of this poetry in his vachanas acts like magical incantation. There is more meaning in it than meets the eye. There is more occult power in his sayings than their obvious meaning tends to convey. The construction of the sentences and the arrangement of the words have a special significance and meaning. Allama Prabhu is a poet-seer, a prophet, a philosopher and a spiritual leader, all rolled into one Great Saint.

Allama Prabhu is a poet-seer, a prophet, a philosopher and a spiritual leader, all rolled into one Great Saint. His sayings – Vachanas – can be set to melodious music and debated and discussed at the gathering of the learned and the wise. During the tumultuous days following the departure of the Sharanas from Kalyana around 1168 and there after for the several hundreds of years, a great majority of Allama’s vachanas were lost. However, we have now been able to collect and collate a few thousand sayings. Undoubtedly, his vachanas are vast and versatile ranging from the simple, pragmatic themes to the subtle, sublime and metaphysical eternal truths. All that is best in the great poets of all times and climes is not what is provincially protracted by the national boundaries but what is universal in its concept and application. It is this universality in Prabhu’s sayings that makes us wiser and better by continually revealing the eternal beauty and truth that God has blessed and deposited in our souls. The world itself is full of poetry of serene sights, soulful sounds and vivid colours – the air vibrating with ethereal forms, the waves dancing to the tune of the melodies, the flames of fire sparkling with heavenly splendour. Poetry is music in words and music is poetry in sound; the mission of poetry is not to make us think but to compel us to truly experience. The greatest poem is not that which is most skilfully woven but that is replete with poesy. Allama’s sayings abound in poesy, thus raising them to the sublime level of poetry.

In the hands of a gifted poet who is a genius, a dry wooden stick becomes an Aaron’s rod, and the sight of a dancing mountain daisy thrills the heart. His sensitive ear senses far-away whispers of eternity, which the untrained souls must travel scores of years before their unsharpened sense could feel the waves. There are many tender and holy emotions roving freely in our minds, which do not assume any definite shape. Similarly, there spring up many rich and lovely flowers with no seed! However, poetry can give a divine shape to these intangible emotions and render pregnant these lovely flowers!! The two common traits of poetry are delicacy and sweetness. Shelley is right when he says that our sweetest songs are those that tell us the saddest thoughts. Thus, poetry is the sister of sorrow; every person who suffers and weeps is a potential poet; every tear a disguised verse and every heart a poem in prospect. Suffering inspires the poets to sing. Suffering, like experience, is a great teacher; it purifies, uplifts and inspires. Woe unto him who lives without suffering. In every pain and suffering, the mystic recognizes the necessary pang of incessant procreation, a series of stages towards an ever-growing perfection. Shri Shankaracharya, the great mystic-philosopher, in a pertinent remark states, “However terrible the suffering may be, you should neither lament nor fear nor even wish to remedy it, but can only endure ti. I say the experience of suffering leads to salvation.” Shri Shankaracharya’s above statement is strongly reminiscent of Shelley’s words.

“To suffer woes which hope thinks infinite

To forgive the wrongs which are darker than death or night.

To defy power which seems omnipotent

To love and bear,

To hope till hope creates from its own wreck

The thing it contemplates.”

It is strange yet true that we learn not so much from joys and pleasures as much from our pain and suffering, for they have lessons to impart and without which one may never learn to appreciate and distinguish the sublimities of life such as compassion, discrimination and dispassion. Sadhu Vasvani uttered a simple yet sublime truth when he said: “Man is an angel fallen to the earth to receive the gift of pain.” Yes, pain or suffering must not be shunned or shunted off but be suffered and endured. For it is life’s gift to the humans, and in accepting it as a part of life and growings up we learn to appreciate the boundless blessings of God. This element of suffering as revealed in the pangs of separation, receives an added momentum in mysticism and mystic poetry. The two moods of mystics, namely Samlesha (elation by union) and Vislesha (depression by separation) are beautifully depicted in Prabhu’s sayings. The mood of Samlesha recalls the elephant’s intoxication rallying in a rut. Prabhu says that there is a peculiar charm in an elephant’s intoxication rallying in a rut (Aneya mada bedagu). When an elephant is affected with rut it becomes so intoxicated by self-consciousness – that it forgets for a while the eternal world. The fear of goad that often haunts the elephant is absent and is replaced by the alternate emotion of joy. Similarly, when the mystic reaches the state of ecstasy, all sense and feeling of duality disappear. In that ecstatic state, the mystic undergoes a unique experience; an experience that destroys all norms and remnants of egoism and the spirit soars to the sublime bliss.

“Fling not Oh Cupid, fling not thy arrow!

How canst thou burn me

Who is already burnt

By the pangs of separation from Guheshwar”.

This saying of Prabhu brings into bold relief the mood of Vislesha. It is in the pangs of separation that divine sorrow overtakes the human soul. The very memory of sorrow is a gentle benediction that broods over man; like the stillness that comes after a dedicated prayer. It is the veiled shadow of sorrow that plucks away one thing after another hobbling and binding men with a sense of ease and security. Yet the vanishing of these beloved objects reveal the abode of their affection and peace of mind. Out of the burning fire of separation, emerge the strongest souls. Martyrs have set their coronation robes glittering with fire and their tears have shown the gates of Heaven to the sorrowful. Thus, sorrow is the initiator that ushers man into the life of the spirit. Huntington’s beautiful remark is worth noting: “Sorrow is our John the Baptist, clad in grim garments with rough arms, a son of the wilderness, baptizing us with bitter tears, preaching repentance and behind comes the gracious, affectionate, healing Lord, speaking peace and joy to the soul.”

Every mystic on the path of realization, experiences elation and depression. Mystic’s love for God takes him on aesthetic waves, taking him high on Union with God and low on separation, marking the alternate stages of yoga. These mystic moods are so deep and intense that they overpower all trials and tribulations, joys and sorrows, depressions and devastations, ups and downs. This observation brings to our mind Milton’s poems – “L’Allegro” and “Il Pensieroso” – the optimistic and the pessimistic moods. The poetic and philosophic description of these two moods by the best minds can hardly match the incomparable depiction of the two moods by Prabhu. These moods of elation and depression represent the dream of Love and Death. The dream of love and death is in reality the Dream of life; it is the Cosmic Drama. Edward Carpenter has titled his mythical work “Dream of Love and Death”. Referring to the Art of Love, he says that this art is not to be trifled with and ignored as such, but it belongs to the realms of psychology, biological science and ultimately to religion. When a mystic dies, he rises triumphantly to love God. In the process of dying, the mystic experiences pain or sorrow. The sorrow or pain born out of the pangs of separation is the price the mystic has to pay to gain the grace of God. Rabindranath Tagore, in his book Gitanjali, sings melodiously of this sorrow as an offering to God and as secret heart of the universe.

“It is the pang of separation that spreads

throughout the universe and gives birth

to shapes innumerable in the infinite sky.

It is this sorrow of separation that

gazes in silence all night from star to

star and becomes lyric among rustling

leaves in rainy darkness of July.

It is this overspreading pain that

deepens into loves and desires into

sufferings and joys in human homes;

and this it is that ever melts and flows

in songs through my poetic heart.

Mother, I shall weave a chain of

pearls for thy neck with tears of sorrow.

The stars have wrought their anklets

of light to deck thy feet,

but mine will hang upon thy breast.

Wealth and fame come from thee

and it is for thee to give or to withold them.

But this my sorrow is absolutely

mine own, and when I bring it to thee

as my offering thou rewardest me with thy grace.”

Throughout the sayings of Prabhu are discernible the sparks and signs of a powerful mind, emancipated from the influence of authority, and devoted to the search of the eternal truth through poesy. The melody of this poetry in his vachanas acts like magical incantation. There is more meaning in it than meets the eye. There is more occult power in his sayings than their obvious meaning tends to convey. The construction of the sentences and the arrangement of the words have a special significance and meaning. Substitution of one synonym for another destroys the intended effect. Unrivalled beauty dawns on repetitious singing of his sayings and the memory becomes impregnated with intrinsic impressions. In the flight of imagination, in the depth of meaning, in the sublimity of expression and in the supernatural regard, Dante comes nearer to Prabhu than Homer or Milton. Dante’s characters are not mere metaphysical abstractions, they are wonderful creations. However grotesque and strange the images may be, he never shrinks from caricaturing them. He is never at a loss for the appropriate words. His description is clear, concise and graphically vivid; he counts the numbers, he scales the height and he measures the metres. The dominant feature of Dante’s poetry is remoteness of the associations, which impresses the readers not so much by what it expresses but what it suggests, not so much by the ideas it directly conveys but by the ideas it implies. However, Prabhu’s poetry distinctly differs from Dante’s in the same way as the hieroglyphs of Egypt differ from the picture writings of Mexico. The images employed by Prabhu have a significance which is often intelligible to the initiated. If the character of Prabhu is distinguished by the loftiness of spirit, that of Dante by the intensity of feeling. The Divine Comedy is deeply touched with sorrow. It is suffused with pathos and with all its moods, it ranges from the homely and humorous to the terrible and sublime. There is poetry that is wholly agreeable. There is poetry that is superbly sublime. There are the pleasures of poetry. There are the ardours of poetry. Valmiki’s poetry is agreeable while Vyas’s is sublime. Among the modern poets of India, Tagore’s writing is agreeable while Shri Aurobindo’s is grand. Savour his poetical grandeur:

“Son of man,

Thou hast crowned thy life

with flowers

That are scentless,

Oh thou golden image

Miniature of bliss

Speaking sweetly, speaking meetly,

Every word deserves a kiss.”

Shri Aurobindo described by J. H. Cousin as a poet-philosopher, has demonstrated once more that poetry is not merely beauty but power; it not only reflects fertile imagination but also creative vision. The undercurrent of grand poetry in the sayings of Prabhu, the philosopher leads us to consider him as a poet. In Prabhu, we see a personality that forces human language to express one of the most sublime visions of the Absolute, which is indescribable. He inherits and fuses into one that loving and artistic reading of reality, the heart of the Agamic lore, and that august concept of the transcendent world, the vital part of the Upanishadic lore. For one, the spiritual world is all love, for the other it is all law. For Prabhu it is both. Prabhu’s vachanas reflect a beautiful vision, the symbolic system of all great mystics. Prabhu is a master of poetic sensibilities. What is it that is alive, grows and vibrates in Prabhu’s sayings? It was his mission to harmonize and spiritualize the human life. To many, this may appear poetically intractable and not amenable to aesthetic treatment. But, Prabhu has transformed philosophical discourses into mystic fervour and created a beautiful reality out of it. Herein lies the greatness of his genius and accomplishments. Many think that philosophical discourses do not nicely lend themselves to poetic proclamations. Virgil and Milton, though inclined to philosophy in their poetic creations, were not really philosophers. Dante, on the other hand, endeavoured and sought to philosophize in his Paradise.

Prabhu, an eternal philosopher, breathes philosophy into his vachanas. What can endow intrinsic, integral impetus to poetic inspiration if it is not the thought of God, soul and immortality? What is it that can strike the deepest chord in man, if it is not the mystery of his own being? Since ordinary man has been trained and taught to subsist on earthly pleasures, he is led to consider poetry as an expression of human joys and sorrows. In India, the Upanishads and the Gita are great philosophical poems. They are out of intellectual reach and realm of common man. These treatises are idolized more as philosophy than as poetry. It is true that Shaiva and Vaishnava poets have sung to the glory of God and divine love. But it is the human significance and manner that touch and move us. The spiritual significance that remains esoteric is a matter of deduction. Prabhu deals with spiritual experiences and presents them in a sublime way, just as he experienced and realized. His thoughts inspire and motivate the reader. Poets generally write about “the heart and its throbs, the vital and its surges in their variations.”

Man is so often and so much enamoured of the pleasures of the “agreeable poetry” that he often forgets the ardours of the “grand poetry”. But, Prabhu is always grand rather than agreeable. His vachanas are full of the ardours of poetry rather than pleasures of poetry. In his classification of literature De Quincey says, “First there is the literature of knowledge and then secondly there is the literature of power. The function of the first is to teach, that of the second is to move; the first is a rudder, the second is a sail. The first speaks to the mere discursive understanding; the second speaks ultimately to the higher understanding or reason.” This reason does not find a place in the domain of “agreeable poetry”. It, however, finds its rightful charm in their spiritual setting and ideal. The modern man in his quest for the sublime, has scouted and belittled the spiritual ideal. The real problem for him has been to live materially before he can hope to live spiritually. The main thing about this problem is that the spiritual ideals and yearning cannot be kept indefinitely in cold storage. The ideal embodies an essential, central truth of man’s existence. It is the preoccupation of the inner being of man. All other ways of curing human ills are faint echoes and diversions of this secret urge. The ideal then declares that it is the spiritual consciousness that upholds and builds up matter and the physical body. Thus, spiritualization of matter has been the one ideal of the Indian culture. The Bible proclaims, “In the beginning there was the Word and the Word was God.” We, then, had better say that the Word was made flesh and the Word was made poetry. The work of the saint is to express the supreme Word in life. To express the Word in speech is the labour of the poet. Allama Prabhu undertook this twin function of the poet and the saint. He amply and justifiably fulfilled both of these functions. The poet has to utter the unutterable if he is to clothe in words the mystic experience of the saint in him. Prabhu has admirably accomplished this. T. S. Eliot who endeavoured to undertake this double function, found it to be a difficult task:

“Words after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only the form, the pattern

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness

But alas,

Words strain crack and sometimes break

Under the burden.”

In Eliot, the faculty of the Saint and poet remains distinct, each with its own reason and rhythm, not fused and moulded into a single pattern of beauty. The poet flies high, very high indeed. At times, he flies low not disdaining the perilous limit of pathos. But the utter poetic ring of the Inferno is difficult to maintain in the Paradiso, unless the poet transforms himself into the Saint as Prabhu did. The world will honour Prabhu not only as a great Sharana but also as a great literary giant; not only as a pre-eminent philosopher-mystic but also as an enlightened artist. Allama Prabhu is doubtless an artist of the first rate caliber, both figuratively and literally speaking. After all, what is art? Art is something that tells us of the “Infinite Passion and the pain of the finite hearts that yearn.” The reading of Prabhu’s sayings will convince us of his skill and craftsmanship in delineation the passion and pain of the finite hearts, of the foibles and follies of the common man, of the serenity and sublimity of the mystic, of the order and arrangement of the transcendence and immanence of God. The fundamental concept of art is to present the world as Idea. This concept of life as the idea lies at the root of the highest forms of art.

As an artist, Prabhu is remarkably a realist, for a true poet is an artist. He has superbly succeeded in his artistic goals, for it is the spiritual enthusiasm that brings forth the catharsis.

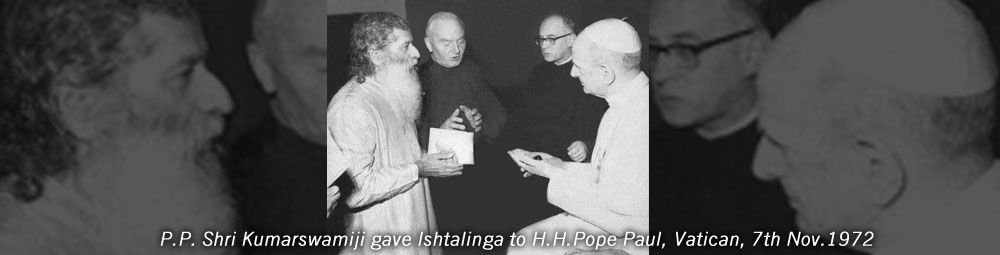

This article – ‘Allama Prabhu – A Literary Genius – I’ – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Prophets of Veerashaivism’.