So long as we view Basava in the context of Lingayatism as a sect we miss his personality and his profound teaching. Though he was born in the Kannada country he belonged to the whole of mankind; for his heart relented for the poor and down-trodden. He taught us one of the main principles of democracy by saying that the roots of the social life are embedded not in the cream of society but in the scum of society. It was his witty saying that the cow does not give milk to him who sits on its back but to him who squats at its feet. With this wide sympathy he admitted high and low alike into his fold. This remarkable admission carried its influence far and wide and stirred the stagnant waters of the land. It rendered the religion all embracing in its sympathy, catholic in its outlook, a perennial fountain of delight and inspiration.’The world is a battle-field, fight your way out’, said Basava.

Basava hailed from a place of the Bijapur District which is now in Karnatak. He flourished in the 12th century and was the Prime Minister to Kinga Bijjala who ruled from 1156 A.D. to 1166 A.D. overt Kalyana which is situated in the Bidar district of Karnataka. Basava was a resolute and independent thinker as also a man of consistent conduct and candid character – a rare instance of powerful will combined with powerful intellect. He was also a mystic, a statesman, a religious reformer, a literary figure and above all an eminent socialist. By the middle of the 12th century he sponsored a movement called Lingayatism or Virashaivism which wrought many changes in the cultural life of India. The movement was not a revivalistic but a revolutionary one since it did not revive the cult of rites and rituals. It introduced a new method of worshipping God in the form of Ishtalinga. It gave freedom of thought and action and free scope for discussion in religious matters. It taught not merely dignity of manual labour but it inculcated into men the spirit of doing any menial work as worship. Thus it gave a great fillip to the development of arts and crafts of the land. It liberated the community from the shackles of groundless fears and irrational superstitions, such as would manifest in the observation of omens and religious pollutions. It did away with caste distinctions and priest-craft and tried to uplift and educate the untouchables. It gave sanctity to the family relations and raised the status of women. It produced a literature of considerable value and enriched the Kannada language of the country. It made the community more humane and at the same time more prone to hold together by mutual toleration. It brought about a synthesis between head, heart and hand. It tended in all these ways to rise the nation generally to a higher level of capacity both of thought and action.

The movement inaugurated by Basava was not a sect with stereotyped ideas but in course of it happened to be so. So long as we view Basava in the context of Lingayatism as a sect we miss his personality and his profound teaching. Though he was born in the Kannada country he belonged to the whole of mankind; for his heart relented for the poor and down-trodden. He taught us one of the main principles of democracy by saying that the roots of the social life are embedded not in the cream of society but in the scum of society. It was his witty saying that the cow does not give milk to him who sits on its back but to him who squats at its feet. With this wide sympathy he admitted high and low alike into his fold. This remarkable admission carried its influence far and wide and stirred the stagnant waters of the land. It rendered the religion all embracing in its sympathy, catholic in its outlook, a perennial fountain of delight and inspiration. He taught in simple language that every individual can work out his own salvation by dedicating himself to the Lord, that in matters of faith the indivious distinctions of caste and colour have absolutely no place, and that the mediation of a priest with all the paraphernalia of rites and rituals has no meaning and efficacy, when the eye of the soul turns round from darkness to light. In order that his gospel may appeal to all alike and may be widely diffused, he adopted Kannada, the native tongue, as the medium of his instruction. Basava himself was a precursor of a new style in Kannada literature. The labours of Basava and his colleagues led to the development of Vachana unique in the cultural history of Karnatak. As a result of this, the national interest was freed from the thraldom of scholastic learning. The language of common people attainted the dignity of a classical tongue, because many a Vachanakara poured out his full heart in profuse strains of unpremediated art.

Basava saw the appalling ignorance and superstition of the masses and traced their root-cause to caste system and idolatry. He did not favour idolatry but advocated strict monotheism, the worship of one and only one God. Caste has been perhaps the great obstacle to social, economic and political progress of India. It has stood in the way of solidarity of the Hindu people and prevented the growth of a compact nation. The caste system is defended on the ground of division of labour, and division of labour is a necessary feature of every civilized society. Basava raised the cry of revolt against caste not because it is a division of labour but because it is a divison of labourers into water-tight compartments. It is a hierarchy in which the division of labourers is graded one above the other. This division of labourers is graded one above the other. This division of labourers is not spontaneous; it is not based on natural aptitudes, but it is founded on the social status of parents. Hence the stratification of occupation and industries. But industry is not static, it undergoes changes; with such changes an individual may be free to change his occupation. Basava advocates not the hereditary profession but pleads for the free choice of occupation. Says he, “A man becomes a blacksmith by heating iron, he becomes a washerman by washing clothes, he becomes a goldsmith by tinking gold, he becomes a Brahmin by reading Vedas.” Is there caste pre-destined, he asks. Caste is not based on the dogma of predestination but it is based on free choice.

One of the mounmental works that Basava did was the establishment of an institution named the Anubhava Mantapa. It was a spiritual as well as social academy presided over by Allama Prabhu, a great spiritual personage. That this rare but monumental institution in the cultural history of India was founded by Basava about 1160 A.D. is corroborated by the sayings of his contemporaries. Anubhava Mantapa is therefore not a fancy but a fact that stands pre-eminent in the history of Lingayatism. It was a nulceus around which gathered persons of all shades, of all professions and of all ranks, ranging from the prince to the peasant, to take part in the deliberations of religious, social, economical and spiritual matters. It is gratifying to learn that amongst the assemblage of these persons numbering about 300 there were nearly sixty women mystics of whom Akka Mahadevi was the becon-light. To this institution we owe that flood of religious literature in Kannada known as Vachana literature unique in the history of Indian culture. From it emerged the Sat-sthala philosophy, the most remarkable and unique feature of the faith. Basava founded this institution mainly to make man realize his place in the scheme of the universe, to breathe new spirit in the then decaying religion, to give woman an equality of status and an independent outlook, to abolish caste distinctions, to encourage occupations and manual labour and above all to countenance simplicity of living and singleness of purpose. The institution would bear eloquent testimony to the genius of Basava whose field of action was as varied as it was vast. It reveals not only his practical wisdom but also the happy blending in him of head, heart and hand. Scholars opine that this institution reminds us of the parliament of religions of Janaka, of the early councils of Ashoka, of the later parliament of religions of Akbar.

Three things emerge from the work of Basava – non-violence, non-explotation and no acceptance of gifts. These were the three cardinal tenets of the social structure as adumbrated by Basava. Basva says non-violence is our creed. Peace is the out-come of non-violence as war is the product of hatred. Peace again is coming to the forefront in the world-politics. To pursue the policy of peaceful co-existence between states, irrespective of their social systems has been the one supreme desire of the major nations. Non-violence has its basis in the spiritual nature of man. Unless the art of politics is brought into touch with spiritual life and experience, it will remain barren and fruitless. Basava attempted to bring politics into touch with spiritual life in his concepts of the welfare state or Kalyana Rajya. The Kalyana Rajya was a society bespeaking the normal expression of human being to ensure sympathy and co-operation, for no man can hope to live alone and be prosperous. Social intercourse is now possible even without blood-relationship and the future awaits the ideal of thought-relationship. Basava’s society was anticipatory of this ideal.

One is apt to overlook the valuable contributions of Basava to economics and socialism. Basava taught the dignity of manual labour by giving it a religious significance. Every kind of manual labour that was run down by the so called high caste persons was looked upon with love and reverence, since it was done in the spirit of service both to God and man. Thus arts and crafts flourished and a new foundation was laid down in the history of the economics of the land. Basava was the first mediaeval prophet to preach that poverty is not a spiritual sin but it is a social evil. It is not a legacy bequeathed to us through sin committed either by us or by our fore-fathers. It is rather an outcome of social conditions. Being urged by this motive he strove hard to set right the economic conditions of the then defunct society. He collected all people belonging to different vocations and laid the foundation of a Brotherhood of labour, the members of which were required to follow these rules:

1. Each member should earn his bread in the sweat of his brow.

2. Each member should take to any work suited to his temperament.

3. Each member should earn only as much money as his needs require. He condemned beggary, even if it is religious, as a curse to life.

Exploitation in one form or the other has been the fate of social life. Great thinkers and reformers were at pains to eradicate it from society. When was it that we came to exploit each other? The day when the strong did say, ‘This is mine and that is yours’. The talk of peace would sound more convincing when nations do not point to each others and say, ‘There lies our future’. Basava was a strict adherent of non-exploitation and tried to bring it into practice in his social structure. He was convinced that explotation dominates all the four spheres of life – economic, political, social and religious. In the economic sphere he saw exploitation between the labourers and the capitalists; he also saw that capital is static and labour, dynamic. As he lived in pre-machinery. He was a partisan of labour and enunciated that labour should be the sole source of value. In the sphere of politics exploitation works under the garb of the ruler and the ruled. In the sphere of social life it is expressed as ill-treatment of the lower class by the higher, and is more manifested as social superiority. And in the religious life, says Basava, exploitation masquerades itself as Guru and Shishya, the relation of which is illustrated by the philosopher’s stone and iron. The illustration of iron and philosopher’s stone, however hoary it may be, bespeaks of the inferiority and superiority complex. He therefore upheld the illustrations of a light lit from another light, the second of which is in no way less than the first. For Basava, socialism was a religion of Trust. So to be trusted is a greater compliment than to be loved. The spirit that keeps up society is mutual trust. Alas! man does not trust man but tempts him, and this temptation is the source of exploitation. Hence the advice: “Better shun the bait than struggle in the snare; for man gains the strength of the temptations he resists.”

Acceptance of gifts has been the mark of civilized society. The covetousness for Dakshina or gits right up from the Vedic times down to the present day is traditional in the history of Indian religion. Later on the Upanishads tried to combat this spirit by saying that true Dakshina consists of penance, charity, rectitude and varacity. Of course this heralds a great change as regards the attitude of man towards the material things of the world. But this change could not hold its sway for a long time, and even if it exerted its influence it was personal. Basava stood for the non-acceptance of gits and his Brotherhood of labour lived up to this tenet literally. Basava was critical of the acceptance of material gifts as it would lower one’s self-reliance and the spirit of independence. He would like to draw to distinction between the gifts of man and the Grace of God; he frowns the former but pines after the latter, for ‘gifts are as the gold which adorns the temple; grace is like the temple that sanctifies the gold’. But he was not unmindful of the glory of the moral gifts, nay, he enjoined upon the members of his Brotherhood to practise them.

Basava was a prophet, that is to say, he was a practical mystic. The word mystic need not frighten us; there is nothing mysterious about mysticism. A mystery is something of which we know that it is, though we do not know how it is. Can science explain all the facts in the universe? No, it can only state them and that is all that we can do with a large proportion of facts that we know. Similarly mysticism is a science which states the relation between man and God. For the thorough-going monist soul is substantially identical with God, and the true object of existence is the making patent of this latent identity, the realization of which finds expression in the Vedantic formula, ‘Thou are that’. But the mystic says that the soul’s union with God is a love-union, a manual inhabitation. This mysterious union in separateness, identity in adaptability of God and soul is a necessary doctrine of all sane mysticism. Mysticism therefore does not allow self-mergence which leaves no place for personality; it allows personality to survive even in union. The call of mysticism upon us is not to lose ourselves into God but to grow into the image of God, to dwell in him and with him, and be a channel of his joy and strength and an instrument of his works. A practical mystic is he, who being purified from all that is impure, transfigured in soul by God’s touch, acts in the world as a dynamo of that divine electricity and sends it thrilling and radiating through mankind, so that humanity may at least become aware of God’s presence and puissance. Are not all the great prophets of the world such practical mystics who radiated into mankind force, light and joy at least to a certain extent? Basava was a prophet, a practical mystic. His great courage and spirit of protestantism, his supreme love and kindness to all, his fearless yet humble adovacy of ennobling doctrines and above all his profound sayings make him the most eminent figure in the mediaeval movement.

Love for Basava as for the mystic is the unique source of the more abundant life which he enjoys and the common factor which unites the finite and the infinite worlds. The whole of creation is the living, changing and growing expression of God’s love and joy. Creation springs from one glad act of affirmation, the ever-lasting yea, perpetually uttered within the depths of the Divine nature. Love which knows no fear, love which knows no bargain, love which is its own ideal is real Bhakti. Man can will nothing but what he loves. His love is the sole and at the same time the infallible spring of his volition, and of all his life’s striving and movement. Love is revealtion of knowledge, it is inspiration in art, it is motive in morality and it is fullness of spiritual joy. The abiding interest of the great Bhakti movement in India lies in its affirmation of the claims of the human heart, and in the moral and spiritual uplife to which it has supplied a stimulus.

Basava, with all his passion for love was a partisan of power. Power in man is so often associated with the crude impulses of egoism that it becomes very difficult to associate power with the Divine. In the complete movement of life, power plays an equal part with love. Power represents the majestic side of the Divine; love, its beatific side. The sweeter rhythm and finer expression of life become possible when the Divine power is established in us. Basava maintained the heroic attitude in all concerns of life. True to the realistic instinct, he could feel that power should not be denied to man, for the organization of life-forces is impossible without it. And in the regulation of cosmic affairs, will and power are great assets. ‘The world is a battle-field, fight your way out’, said Basava. In the economy of nature, power has its proper place. The Divine is not all love, it is also stern Will and dominating power. The forces help each other in the complexity of life and its adjustments. Basava abolished the supposed antithesis between love and power, between Bhakti and Shakti and gave each its proper place in the scheme of his religion.

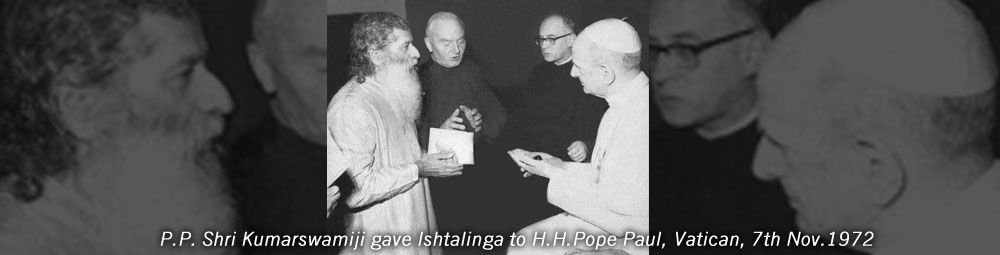

This article – Basava and Mission – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Mirror of Virashaivism’.