A genuine reformer appears once in a millennium. He appears to review the past history of our social conditions and to set them in a new order. His task is not one of a revolution but of readjustment. What we observe is partly the same scene but in a different and more distant perspective. There are new and strange objects in the foreground to be drawn accurately in proportion to the more familiar ones, which now approach the horizon, where all but the most eminent become invisible to the naked eye.

The movement of reformation inaugurated by Basava had its far reaching effect upon the social life of the nation. So long as we view Basava in the context of Veerashaivism, we miss his personality and his profound teaching. Though he was born in Karnataka, he belonged to the whole of mankind for his heart relented for the poor and downtrodden everywhere. He taught us one of the main principles of Democracy by saying that the roots of social life are embedded not in the cream of society but in the scum of society.

Basava flourished in the 12th century in Karnataka. He was a Prime Minister to King Bijjala who ruled from 1157 to 1167 over Kalyana, a city of historic importance. Basava was indeed a great prophet; for in him we find the combination of rare qualities. He was a mystic by temperament, an idealist by choice, a statesman by profession, a man of letters by taste, a humanist by sympathy and a social reformer by conviction. Basava strove hard to bring about reformation in Hinduism into which social evils had crept in. The social and cultural conflicts which had been going on in India from ancient days were stimulating a new foment within the Hindu society. At the time of Basava there were apologists who had been giving a new interpretation to the irrational religious practices and form of thought. But Basava with a courageous frankness acknowledged the prevailing evils of the Hindu society and suggested ways and means to create a new orientation. His suggestions may be stated as follows:

1. The Hindu Society should leave its smug, satisfaction and become critical of itself.

2. Unity can only be achieved by social and cultural rapprochement.

3. A revolt against the exploiting forces is necessary for the preservation, protection and security of social democracy.

A genuine reformer appears once in a millennium. He appears to review the past history of our social conditions and to set them in a new order. His task is not one of a revolution but of readjustment. What we observe is partly the same scene but in a different and more distant perspective. There are new and strange objects in the foreground to be drawn accurately in proportion to the more familiar ones, which now approach the horizon, where all but the most eminent become invisible to the naked eye. The exhaustive reformer will be able to sweep the distance and gain an acquaintance with the minute objects present in the landscape, with which to compare minute objects close at hand. He will be able to gauze the position and proportion of the forces surrounding us in the whole vast panorama.

The movement of reformation inaugurated by Basava had its far reaching effect upon the social life of the nation. So long as we view Basava in the context of Veerashaivism, we miss his personality and his profound teaching. Though he was born in Karnataka, he belonged to the whole of mankind for his heart relented for the poor and downtrodden everywhere. He taught us one of the main principles of Democracy by saying that the roots of social life are embedded not in the cream of society but in the scum of society. It is his witty saying that the cow does not give milk to him who sits on its back but it gives milk to him who squats at its feet. With this wide sympathy, he admitted high and low alike into his fold. This remarkable admission carried its influence far and wide and stirred the stagnant waters of the land. The caste system is the negation of democratic society. But the Anubhav Mantapa established by Basava laid down the foundation of social democracy. A democratic society is one in which all enjoy social rights and privileges without any barriers of class distinctions. Birth, wealth, caste or creed do not determine the status of man. This means faith in the dignity of man and the belief that a common man is as good a part of society as a man of status. Basava believed that man becomes great, not by his birth but by his worth to the society.

Basava raised the cry of revolt against the static form of society. He proclaimed that all members of the state are labourers, some may be intellectual labourers and others may be manual labourers. Even the Jangamas were not exempted from doing labour. Thus all the members of the State ranging from the Prime Minister to the menial servant, from the peasant to the priest were enjoined to do Kayaka. He would often say that the State is the school for the citizen; the vocations and professions are educational devices through which the clerk, the teacher, the doctor, the minister, are learning while they are labouring for the state. Basava was a Prime Minister to King Bijjala who was an usurper and a despot, yet he did not mince matters in convincing this despotic monarch that the solidarity of his Kingdom would depend upon the strength and character of his subjects. He placed practice before precept and his own life was of rigid rectitude. Basava brought home to his countrymen the lesson of self-purification. He raised the moral level of the public life in the country and he insisted that the same rules of conduct applied to the administrators as to the individual members of the society.

Basava attempted to bring politics in touch with ethics in his concept of the welfare state or Kalyana Rajya. Unless politics is brought in touch with ethics, it will remain barren and fruitless. Mazzini upheld the same idea and pleaded for the harmony of politics and ethics. Gandhiji also maintained the same view for it is said that Gandhiji revolutionized politics by moralizing it and devised a technique based upon truth and non-violence for the solution of individual and group problems. Man can only pursue his moral ends while living in the state. Aristotle rightly said that a good citizen is possible in a good state and that a bad state makes bad citizens while the state came into existence for the sake of good life. Good life is therefore the end of the state. What is morally wrong cannot be politically right because there cannot be a good state where wrong ethical ideals prevail. An ideal sphere of state activity cannot be determined without moral considerations. The great question is to discover not what governments prescribe but what they ought to prescribe. Today man in his arrogance is scouting and belittling the moral considerations and ethical ideals. The divorce of politics from ethics has landed mankind in chaos and confusion, in moral crisis which is calculated to mar the beauty and chastity of life.

Basava taught the dignity of manual labour by insisting on work as worship. Every kind of manual labour that was looked down by the so called high caste persons was looked upon with love and reverence. Thus arts and crafts flourished and a new foundation was laid down in the history of the economics of the land. Ruskin in his ‘Unto the Last’, Carlyle in his ‘Past and Present’ and Tolstoy in his ‘What I Believe’ have stressed the importance of work, and have emphasized the worth of manual labour. Of these three, Carlyle is more vehement. Listen to his ringing words, “The latest gospel in this world is: Know thy work and do it. Know thy self long enough that poor self of thine tormented thee; Thou wilt never get to know it, I believe. Think it not thy business, this knowing of thyself; thou work at it like a Hercules, that will be thy better plan.” Basava already knew this better plan, for he had collected all people belonging to different vocations and laid the foundation of a brotherhood of labour, the members of which were required to follow these rules: Each member should earn his bread by the sweat of his brow. Each member should take up work which suits to his temperament and each member should earn daily as much money as his needs required. He condemned beggary as a curse to life.

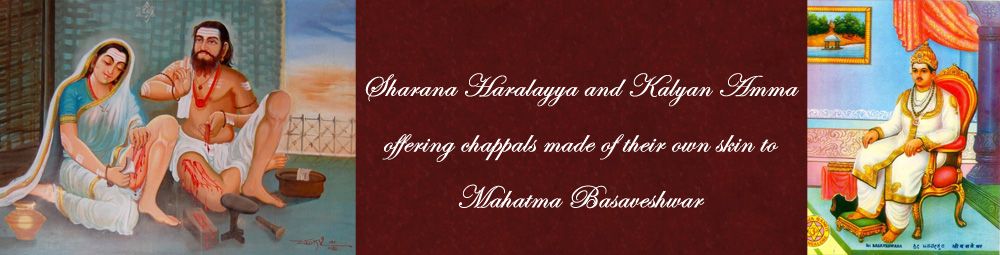

Basava formed peoples’ committees representing various vocations such as agriculture, horticulture, tailoring, weaving, dying, carpentry etc. All vocations were regarded as of equal value and the members belonged to all sorts of vocations. Thus Jedara Dasimayya was a weaver, Shankar Dasimayya a tailor, Madival Machayya a washerman, Myadar Ketayya a basket maker, Kinnari Bommayya a goldsmith, Vakkalmuddayya a farmer, Hadap Appanna a barber, Jedar Madanna a soldier, Ganada Kannappa an oilman, Dohar Kakkayya tanner, Mydar Channayya a cobbler and Ambigara Chowdayya a ferryman. There were members of the fair sex such as Sathakka, Ramavve, Somavve, with their respective vocations. The curious thing was that all these and many more have sung the Vachanas regarding their vocations in a very suggestive imagery.

In the organization of social life, politics, economics and religion are the three great regulative factors of human endeavour. At each epoch one or the other predominates; if religion was predominant then in the times of Basava, politics is predominant now in our times. In the social life of a man, politics, economics and religion henceforth cease to be regarded as mainly separate problems. They now present themselves as one and the same coordinated problem. Political liberty, economic equality and religious fraternity are the triple goals of human society. But the union of liberty and equality can only be achieved by the power of human brotherhood and it cannot be founded on anything else. For this, human brotherhood or religious fraternity is not a matter of physical kinship or of vital association, or of intellectual agreement; it is indeed a recognition of the inner spiritual unity. In the present day socialism/communism, the vision of this spiritual unity and universal brotherhood is lacking.

Socialism of the true type must, in the opinion of Basava, take into account not only the economic values but also the moral and spiritual ones. Modern socialism has erected by isolating the economic man and relegating the moral and spiritual values to the lumber room. The idea of God as the creator and father of all mankind is in the moral world what gravitation is in the natural world. It holds all together and causes them to revolve around a common centre. Take this away, men drop apart and moral chaos would then be the order of the day. This is what we are witnessing in our present day social life. It is mutual love and cooperation among the members of society based on the moral and spiritual values that contributes to the real growth of human personality. Hatred or violence in any shape or form cannot lead to any kind of lasting peace of socio-economic reconstruction.

Basava condemned idolatry as leading to the subservience of will to material things. But we are living in the most dangerous idolatry of all ages – the deification of the state. The dangers of economic and political despotism inherent in a system of centralized control of the entire system of production are becoming more and more acute and agonizing. Any centralized form of government is bound to be oligarchical independency. We are told that the state will wither away; neither history nor psychology afforded any warrant for this conclusion, until recently. However, recent events in Eastern Europe and Russia – the so called Iron Curtain countries – have extolled the virtues of human spirit and freedom. This in itself and by itself lends credence to the above statement. Any policy of reconstruction that is to be of real value must aim at decentralization, for decentralization and democracy are the two pillars of sane spiritualistic socialism.

Man needs a principle for his conduct and character or else he with his passions, prejudices and partial light becomes himself the measure. The application of the motto, man is the measure of all things, to the social life has ultimately driven humanity to the crass doctrine that might alone is right and that success justifies everything. If we would have humanity advance we must buffet this motto and build the social life of humanity upon the fundamental principle of truth. Humanity must remain true and loyal to the principle of truth which may not be dispensed with, in an anxious desire to achieve certain ends however laudable they may be. It is for this reason that Basava warned us by saying that every violation of truth is a stab at the health of human society. Truth and good are at the basis of society, the ignoring of which will reduce the social life of man to a pack of hungry wolves. In his social structure Basava gave to truth the first place, for he was aware that truth is the foundation of all knowledge and the cement of all societies. Since truth, like light travels in straight lines, Basava stressed straigthforwardness, simplicity, sincerity, humility and the like moral qualities, as the essential condition of social life. According to Democritus, truth lies at the bottom of a well, the water of which serves as a mirror in which objects may be reflected. Alas! We have seen however that some reformers in seeking the truth, in order to pay homage to it, have seen their own image and adored it instead. But Basava saw deep down into the well and there he envisaged the truth and built an institution named Anubhava Mantap which was the only field where both of the sexes could meet on terms of equality, the arena where character could be formed and studied, the cradles of reasoned opinion, the crucible of ideas, at once a school and a theatre, spectre and crown of aspiration, the tribunal which unmasked pretension and stamped real merit.

The Times of India in its issue dated 17-5-1918, paid a glowing tribute to Basava. “It was the distinctive feature of his mission that while illustrious religious and social reformers in India before him had each laid his emphasis on one or other items of religion and social reform, either subordinating more or less other items to it or ignoring them altogether, Basava sketched and boldly tried to work out a large and comprehensive programme of social reform with the elevation and independence of womanhood as its guiding point. Neither social conferences which are usually held in these days in several parts of India, nor Indian social reformers, can improve upon that programme as to the essentials. The present day social reformer in India is but speaking the language and seeking to enforce the mind of Basava.”

The movement initiated by Basava through ‘Anubhava Mantapa’ became the basis of religion of love and faith. It gave rise to a system of ethics and education at once simple and exalted. It inspired ideals of social and religious freedom, such as no previous faith of India had done. In the medieval age which was characterized by inter communal jealousy, it helped to shed a ray of light and faith on the homes and hearts of people. It rendered the Hindu religion all embracing in its sympathy, catholic in its outlook, a perennial fountain of delight and inspiration. The movement gave a literature of considerable value in the vernacular language of the country, the literature which attained the dignity of a classical tongue. It eliminated the barriers of caste and removed untouchability. It raised the untouchable equal to that of the high born. It gave sanctity to the family relations and raised the status of womanhood. It undermined the importance of rites and rituals, of fasts and pilgrimages. It encouraged learning and contemplation on God by means of love and faith. It deplored the excesses of polytheism and developed the plan of monotheism. It tended in many ways to raise the nation generally to a higher level of capacity both in thought and action.

This article – Basava – The Great Socio-Religious Reformer – is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji-s book, ‘Prophets of Virashaivism’.