Jyotirlinga and Ishtalinga, the self of cosmos and the self of man are identically the same and so are one. The self of man is termed Anga which is Chit-rupa, the pure Conscient; the self of cosmos is termed Linga which is Sat-rupa, the pure Existent; and that Anga and Linga are one and the same is proved by the subjective mode of worship, that is, Aham-grahopasana. The realization of the one existence in the apparent infinite multiplicity and complexity through self-awareness, is Samarasya, delight equal and equable. Samarasya is therefore Ananda-rupa. Linganga-samarasya then is a technical name of the Lingayat religion for the highest God-head, Sachhidananda.

Three things emerge from the labour of Prof. Sakhare, three things of which Navakalyana Math has already stood as a champion: Lingayatism is the faith professed and followed by the Karnatak Virashaiva; Basava is the founder of this faith and Vachana-shastra are the scriptures that embody the principles of Lingayatism.

Stout defines consciousness as the awareness we have of ourselves and of our own experiences, as states of the Self – an inner sense – the function by which we perceive the mind and its processes, as the sight perceives the material facts. Father Maher defines it as the mind’s direct intuitive and immediate knowledge either of its own operations or of something other than itself acting upon it; in other words, the energy of the cognitive act, and not the emotional or volitional acts as cognized. The definition of consciousness, according to two famous psychologists Stout and Maher, approximates to some extent to the Indian idea which holds it as Samvit, self-awareness , which is Svayam-prakasha, self-illuminating. Perception, emotion and conation are functions of the mind that take place according to mental laws, whether they are or are not illuminated by the light of consciousness. In ordinary psychic experience, this light of consciousness is inextricably interwoven with the functions of the mind; and can be discerned only when it is separated from the mind and contemplated apart from its functions. This pure consciousness (Aruhu – kannada) as apart from the unconscious (Maruhu – kannada) or personal consciousness in the words of William James, is Chit. William James is right in so far as he makes a distinction between pure consciousness and personal consciousness; but on account of his vision being blurred by Pragmatism, he could see consciousness as a perpetual stream and not as a steady light that knows no change.

Consciousness is Spirit that has an inherent power of illuminating the mental and bodily functions, which would otherwise remain unconscious. The mind of man is an organ composed of subtle matter and is not immaterial or spiritual. Sensation, perception, volition etc. are in Western philosophy called subjective states and treated as non-material. Indian philosophy analyzes them into two factors, namely,

1) a mental process internal but not subjective and

2) the accompaniment of consciousness illumining

the process. The first is material and the second is immaterial. Mental processes are variously classed: the Sankhya attributes to the mind all psychic life while the Vaishesika regards it merely as an organ of attention. But almost all systems of Indian philosophy are agreed in regarding mind as matter. It is difficult to realize mind to be matter because of the fact that it derives a pseudo-subjectivity on account of its being an inner organ. When our muscles act our consciousness accompanies the action; but we can in thought separate the consciousness from the muscular action and realize the latter as a phenomena of matter. But each man can study mental action only in the operation of his own mind; and as these are accompanied by the light of his own consciousness, the separation of these two and the appreciation of the difference of the nature of consciousness and of mental action, becomes a matter of difficulty.

Perception then should be clearly distinguished from apperception or consciousness, Plato and Aristotle use such phrases as ‘the seeing of sight’, ‘the thinking of thought’ to indicate consciousness apart from mental functioning. The Kena Upanishad uses strikingly similar phrases ‘what speech does not enlighten but what enlighten speech’ etc. Plotinus, among ancient philosophers first clearly formulated this distinction and calls apperception by the name of Parakolonthesis which is strongly reminiscent of Chit-prakasha. “Intelligence is the one thing and the apprehension of intelligence is another. And we always perceive intellectually, but we do not always apprehend that we do so.” The idea that consciousness is not a necessary concomitant of mental operations is first clearly enunciated in modern European philosophy by Leibniz. “As a matter of fact our soul has the power of representing to itself any form of nature whenever the occasion comes for thinking about it; and I think that this activity of our soul is, so far as it expresses some nature, form or essence, properly the idea of the thing. This is in us and is always in us whether we are thinking of it or not.” Leibniz means to say that all psychic life is in itself unconscious except in so far as the light of consciousness illuminates it and manifests it to the knower. It is this self-luminous consciousness that goes by the name of Jyotirlinga.

Jyotirlinga and Ishtalinga, the self of cosmos and the self of man are identically the same and so are one. The self of man is termed Anga which is Chit-rupa, the pure Conscient; the self of cosmos is termed Linga which is Sat-rupa, the pure Existent; and that Anga and Linga are one and the same is proved by the subjective mode of worship, that is, Aham-grahopasana. The realization of the one existence in the apparent infinite multiplicity and complexity through self-awareness, is Samarasya, delight equal and equable. Samarasya is therefore Ananda-rupa. Linganga-samarasya then is a technical name of the Lingayat religion for the highest God-head, Sachhidananda. The Self of all whether in man or cosmos is an infinite, indivisible existence; of that existence the essential nature is infinite, imperishable force of self-conscious being; and of that self-consciousness the essential nature is, again, an infinite inalienable delight of being. God is Sachhidananda. He manifests himself as infinite existence of which the essentiality is consciousness, of which again the essentiality is self-delight. Delight cognizing variety of itself seeking its own variety, as it were, becomes the universe. “If there were not”, says the Taittariya Upanishad, “this all encompassing ether of delight of existence in which we dwell, if that delight were not our ether, then none could breathe, none could live.” The cosmic existence of which we are a part is in its most obvious view a movement of force; but that force on close scrutiny proves to be a constant and yet always mutable rhythm of creative consciousness. And this rhythm is in its essence a play of the infinite delight of being ever busy with its own innumerable self-representation. The world-process then, is not a chaos as the materialist holds, but a fairly charming cosmos as the mystic observes. “Creation springs from one glad act of affirmation, the Ever lasting Yea, perpetually uttered within the depths of Divine Nature�. The whole creation is the play of the Eternal Lover, the living, changing, growing expression of God’s love and joy”. It is participation in God’s love and joy, penetration in the One Infinite Life that is in the objective of Lingayat religion.

The Divine Existence is pure and unlimited being in possession of all itself, it is Sat; whatever it puts forth in its limitless purity of self-awareness is truth of itself, Satya. The Sat in itself is a spaceless and timeless absolute of conscious existence that is bliss; but the cosmos is, on the contrary, an extension in space and time, a movement, a working-out, a development of relations and possibilities. Then there must be a power of knowledge and will which out of infinite potentiality determines relations, develops the results out of the seed, rolls out the mighty rhythms of cosmic Law. This power indeed is nothing else than the Force of Sat itself, it is Vimarsha-shakti. It creates nothing which is not in its own self-existence, and for that reason all cosmic and individual law is a thing not imposed from outside but from within. All development is therefore self-development, all seed and result are a seed of truth of things and result of that seed determined out of its potentialities. In the universe there is then a constant relation of oneness and multiplicity; both between the One and the Many, and among the many themselves there is the possibility of an indefinite variety of relations. These relations are determined, as we have seen, by the inherent power of the Divine Truth. They exist at first as conscious relations between individual souls; they are then taken up by them and used as a means of entering into conscious relations with the Truth. It is this entering into various relations with the One Truth that is the object and function of Religion. All religions are justified by this essential necessity and Lingayat religion is no exception to this.

We may state the object and function of Religion in another way, by saying that Truth is the perception of such a relation and proportion in apparent diversity that this becomes a realized and harmonious unity. There must necessarily be degrees of this perception and it is this graded perception of Truth that justifies the necessity of Sat-sthala, six steps of self-realization, in Lingayat religion. The final perception of the unity of the whole universe would be the absolute Truth and therefore absolute Reality. Such a final perception, however, would not only transcend anything that we know as consciousness. Our perception of Truth or Reality will grow clearer and fuller as we approach to a consciousness of the Unitary nature of all that enters into our experience. We may, by a progressive expanding or a sudden luminous transcendence, mount up to this Truth in unforgettable moments or dwell in it during hours or days of greatest super-human experience. When we descend again, there are doors of communication which can keep always open or reopen even though they should constantly shut. But to dwell there permanently on the last and highest summit of the Divine Truth is in the end the supreme ideal for our evolving human consciousness. And this ideal is nothing short of at-one-ment or Samarasya, when the will of Anga becomes united with the will of Linga – which perfect union reveals itself not in self-annulment but in self-fulfillment. Read Urilinga Peddi’s saying which is pregnant with the soul of Lingayat religion. (There is a footnote in Kannada with this sayings)

A religion in its esoteric-sense, is essentially Mysticism suggestive or expressive of a unitary consciousness that transcends the limitations of intellect. William James speaks eloquently of this characteristic. This over-coming of all the usual barriers between the individual and the Absolute is the great mystic achievement. In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness. This is the ever-lasting and triumphant mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of clime and creed. In Hinduism, in Neo-Platonism, in Sufism, in Christian Mysticism, in Whitmanism we find the same recurring note, so that there is about mystical utterances an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think, and which brings it about that mystical classic have, as has been said, neither birthday nor native land. Perpetually telling of the unity of man with God, their speech antidates languages and they do not grow old. Linganga-samarasy, bereft of its technique is mysticism pure and simple that echoes the ancient nay, eternal Wisdom.

But religion has its exoteric side also; as exoteric it is a conventional expression of formal belief. If the esoteric side is the soul of religion the exoteric is its form. Forms of religion, like every thing else in this world of forms, must change and decay. They will have their way and cease to be, as knowledge grows in gigantic strides. New religions, so called crop up and overlap the decay of old forms and formulas. New teachers, new hieophants arise, and the new wine must be put into new bottles. Yet the old forms may and must persist for many an age. They do so in virtue of their acquired momentum and vested interest as well as from the fact that each does actually, for the time being, express a fundamental fact in human experience. Gautama Buddha was a reformer of Brahmanism and the laws of Manu; yet Brahmanism still holds sway over millions of souls. Not-withstanding Christianity as a reformation of the Jewish religion and the Law of Moses, Judaism is still the religion of millions of followers and Mosaic tradition. And Basava was a reformer of Shaivism and a revolter of Varnashrama, yet Shaivism and Varnashrama have had their spell over millions and millions of souls.

Basava is the founder of Virashaivism in the sense in which Buddha is of Buddhism and Christ of Chritianity. Prof. M.R. Sakhare is clear and emphatic on this point, “To the solution of the problem – who is the founder of the Virashaiva faith? – we have a clue in the very word ‘Virashaiva’. By the time the 12th century was ushered in Jainism and Vaishanivism had gained ascendancy. Shaivism in the South had reached a crisis and time had come for it to rise or to fall. But down it was not to go; for by the time the century had half passed there shot into space a great hero who revolutionized the Shaivite faith in a short space of time. The attempt was heroic and the achievement was brilliant. Shaivism rose triumphant over the trammels of Varnasharma and the result was Virashaivism. The hero happened to be the Prime Minister of the then King of Karnatka. He was a Kannada man and what wonder if Kannada become the language of the scriptures of the new heroic religion and Karnataka become the home of the new faith came to be heroically founded and that is why it has come to be called Virashaiva religion, meaning the heroic Shaiva faith. That was how again Basava became the King of a great religion though the Premier of a little province.”

Three things emerge from the labour of Prof. Sakhare, three things of which Navakalyana Math has already stood as a champion: Lingayatism is the faith professed and followed by the Karnatak Virashaiva; Basava is the founder of this faith and Vachana-shastra are the scriptures that embody the principles of Lingayatism (Quintessence of Lingayatism).

– OM SHANTI | OM SHANTI | OM SHANTIHI –

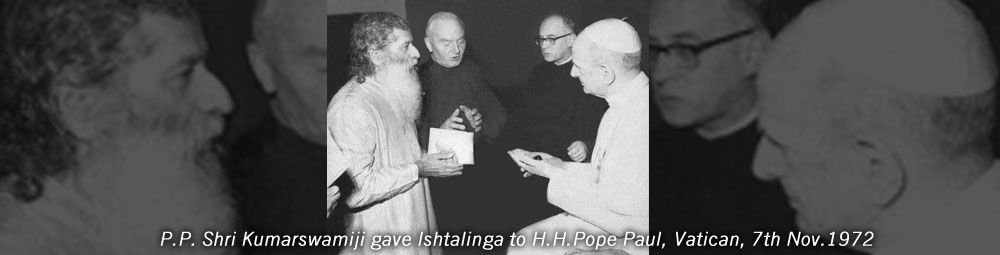

This article ‘Quintessence of Lingayat Religion – II’ is taken from H.H.Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswamiji’s book, ‘The Virashaiva Philosophy & Mysticism’.